Martin Luther

- Died:

- February 18, 1546, Eisleben (aged 62)

- Notable Family Members:

- Son of Hans, copper miner and smelter

- Son of Margaretta

- Brother of 6 or 7 siblings

- Spouse of Katerina von Bora

- Father of six children, four of whom survived to adulthood

- Subjects Of Study:

- Bible

- Lutheranism

- real presence

- authority

- justification

- Role In:

- Colloquy of Marburg

- Reformation

- Education:

- Local Latin school in Mansfeld, Saxony

- Brethren of the Common Life in Magdeburg, starting age 13

- School in Eisenach

- University of Erfurt, 1501

- University of Wittenberg

- On the Web:

- BBC Sounds - Martin Luther and the Reformation (Dec. 09, 2024)

Who was Martin Luther?

What is Lutheranism?

What was radical about Martin Luther’s teachings?

What implications did Martin Luther’s work have for realms other than the religious?

Did Martin Luther have a family?

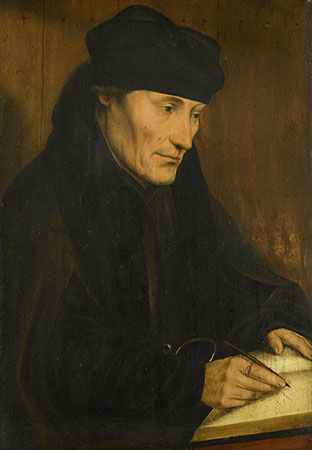

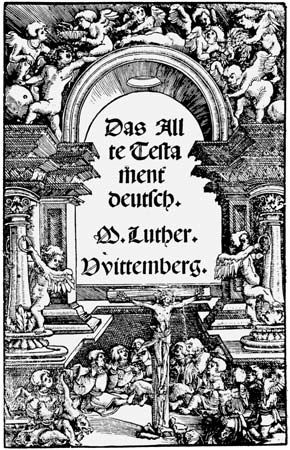

Martin Luther (born November 10, 1483, Eisleben, Saxony [now in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany]—died February 18, 1546, Eisleben) was a German theologian and religious reformer who was the catalyst of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Through his words and actions, Luther precipitated a movement that reformulated certain basic tenets of Christian belief and resulted in the division of Western Christendom between Roman Catholicism and the new Protestant traditions, mainly Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism, the Anabaptists, and the anti-Trinitarians. He is one of the most influential figures in the history of Christianity.

Early life and education

Early life

Soon after Luther’s birth, his family moved from Eisleben to the small town of Mansfeld, some 10 miles (16 km) to the northwest. His father, Hans Luther, who prospered in the local copper-refining business, became a town councillor of Mansfeld in 1492. There are few sources of information about Martin Luther’s childhood apart from his recollections as an old man; understandably, they seem to be colored by a certain romantic nostalgia.

Luther began his education at a Latin school in Mansfeld in the spring of 1488. There he received a thorough training in the Latin language and learned by rote the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, and morning and evening prayers. In 1497 Luther was sent to nearby Magdeburg to attend a school operated by the Brethren of the Common Life, a lay monastic order whose emphasis on personal piety apparently exerted a lasting influence on him. In 1501 he matriculated at the University of Erfurt, at the time one of the most distinguished universities in Germany. The matriculation records describe him as in habendo, meaning that he was ineligible for financial aid, an indirect testimonial to the financial success of his father. Luther took the customary course in the liberal arts and received the baccalaureate degree in 1502. Three years later he was awarded the master’s degree. His studies gave him a thorough exposure to Scholasticism; many years later, he spoke of Aristotle and William of Ockham as “his teachers.”

Conversion to monastic life

Having graduated from the arts faculty, Luther was eligible to pursue graduate work in one of the three “higher” disciplines—law, medicine, or theology. In accordance with the wishes of his father, he commenced the study of law. Proudly he purchased a copy of the Corpus Juris Canonici (“Corpus of Canon Law”), the collection of ecclesiastical law texts, and other important legal textbooks. Less than six weeks later, however, on July 17, 1505, Luther abandoned the study of law and entered the monastery in Erfurt of the Order of the Hermits of St. Augustine, a mendicant order founded in 1256. His explanation for his abrupt change of heart was that a violent thunderstorm near the village of Stotternheim had terrified him to such a degree that he involuntarily vowed to become a monk if he survived. Because his vow was clearly made under duress, Luther could easily have ignored it; the fact that he did not indicates that the thunderstorm experience was only a catalyst for much deeper motivations. Luther’s father was understandably angry with him for abandoning a prestigious and lucrative career in law in favor of the monastery. In response to Luther’s avowal that in the thunderstorm he had been “besieged by the terror and agony of sudden death,” his father said only: “May it not prove an illusion and deception.”

By the second half of the 15th century, the Augustinian order had become divided into two factions, one seeking reform in the direction of the order’s original strict rule, the other favoring modifications. The monastery Luther joined in Erfurt was part of the strict, observant faction. Two months after entering the monastery, on September 15, 1505, Luther made his general confession and was admitted into the community as a novice.

Luther’s new monastic life conformed to the commitment that countless men and women had made through the centuries—an existence devoted to an interweaving of daily work and worship. His spartan quarters consisted of an unheated cell furnished only with a table and chair. His daily activities were structured around the monastic rule and the observance of the canonical hours, which began at 2:00 in the morning. In the fall of 1506, he was fully admitted to the order and began to prepare for his ordination to the priesthood. He celebrated his first mass in May 1507 with a great deal of fear and trembling, according to his own recollection.

Doctor of theology

But Luther would not settle for the anonymous and routine existence of a monk. In 1507 he began the study of theology at the University of Erfurt. Transferred to the Augustinian monastery at Wittenberg in the fall of 1508, he continued his studies at the university there. Because the university at Wittenberg was new (it was founded in 1502), its degree requirements were fairly lenient. After only a year of study, Luther had completed the requirements not only for the baccalaureate in Bible but also for the next-higher theological degree, that of Sententiarius, which would qualify him to teach Peter Lombard’s Four Books of Sentences (Sententiarum libri IV), the standard theological textbook of the time. Because he was transferred back to Erfurt in the fall of 1509, however, the university at Wittenberg could not confer the degrees on him. Luther then unabashedly petitioned the Erfurt faculty to confer the degrees. His request, though unusual, was altogether proper, and in the end it was granted.

His subsequent studies toward a doctoral degree in theology were interrupted, probably between the fall of 1510 and the spring of 1511, by his assignment to represent the observant German Augustinian monasteries in Rome. At issue was a papal decree by Pope Julius II that had administratively merged the observant and the nonobservant houses of the order. It is indicative of Luther’s emerging role in his order that he was chosen, along with a monastic brother from Nürnberg, to make the case for the observant houses in their appeal of the ruling to the pope. The mission proved to be unsuccessful, however, because the pope’s mind was already made up. Luther’s comments in later years suggest that the mission made a profoundly negative impression on him: he found in Rome a lack of spirituality at the very heart of Western Christendom.

Soon after his return Luther transferred to the Wittenberg monastery to finish his studies at the university there. He received his doctorate in the fall of 1512 and assumed the professorship in biblical studies, which was supplied by the Augustinian order. At the same time, his administrative responsibilities in the Wittenberg monastery and the Augustinian order increased, and he began to publish theological writings, such as the 97 theses entitled Disputation Against Scholastic Theology.

Although there is some uncertainty about the details of Luther’s academic teaching, it is known that he offered courses on several biblical books—two on the book of Psalms—as well as on St. Paul’s epistles to the Romans, the Galatians, and the Hebrews. From all accounts Luther was a stimulating lecturer. One student reported that he was

a man of middle stature, with a voice that combined sharpness in the enunciation of syllables and words, and softness in tone. He spoke neither too quickly nor too slowly, but at an even pace, without hesitation and very clearly.

Scholars have scrutinized Luther’s lecture notes for hints of a developing new theology, but the results have been inconclusive. Nor do the notes give any indication of a deep spiritual struggle, which Luther in later years associated with this period in his life.