crucifixion

- Related Topics:

- capital punishment

- cross

- crucifix

- Crucifixion

crucifixion, an important method of capital punishment particularly among the Persians, Seleucids, Carthaginians, and Romans from about the 6th century bce to the 4th century ce. Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished it in the Roman Empire in the early 4th century ce out of veneration for Jesus Christ, the most famous victim of crucifixion.

Punishment

There were various methods of performing the execution. Usually, the condemned man, after being whipped, or “scourged,” dragged the crossbeam of his cross to the place of punishment, where the upright shaft was already fixed in the ground. Stripped of his clothing either then or earlier at his scourging, he was bound fast with outstretched arms to the crossbeam or nailed firmly to it through the wrists. The crossbeam was then raised high against the upright shaft and made fast to it about 9 to 12 feet (approximately 3 metres) from the ground. Next, the feet were tightly bound or nailed to the upright shaft. A ledge inserted about halfway up the upright shaft gave some support to the body; evidence for a similar ledge for the feet is rare and late. Over the criminal’s head was placed a notice stating his name and his crime. Death ultimately occurred through a combination of constrained blood circulation, organ failure, and asphyxiation as the body strained under its own weight. It could be hastened by shattering the legs (crurifragium) with an iron club, which prevented them from supporting the body’s weight and made inhalation more difficult, accelerating both asphyxiation and shock.

Crucifixion was most frequently used to punish political or religious agitators, pirates, slaves, or those who had no civil rights. In 519 bce Darius I, king of Persia, crucified 3,000 political opponents in Babylon; in 88 bce Alexander Jannaeus, the Judaean king and high priest, crucified 800 Pharisaic opponents; and about 32 ce Pontius Pilate had Jesus of Nazareth put to death by crucifixion.

Crucifixion of Jesus

The account of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion in the Gospels begins with his scourging. The Roman soldiers then mocked him as the “King of the Jews” by clothing him in a purple robe and a crown of thorns and led him slowly to Mount Calvary, or Golgotha; one Simon of Cyrene was allowed to aid him in carrying the cross. At the place of execution he was stripped and then nailed to the cross, at least nailed by his hands, and above him at the top of the cross was placed the condemnatory inscription stating his crime of professing to be King of the Jews. (The Gospels differ slightly in the wording but agree that the inscription was in “Hebrew,” or Aramaic, as well as Latin and Greek.) On the cross Jesus hung in agony. The soldiers divided his garments and cast lots for his seamless robe. Various onlookers taunted him. Crucified on either side of Jesus were two convicted thieves, whom the soldiers dispatched at eventide by breaking their legs. The soldiers found Jesus already dead, but, to be certain, one of them drove a spear into his side, from which poured blood and water. He was taken down before sunset (in deference to Jewish custom) and buried in a rock-hewn tomb.

Crucifixion in art

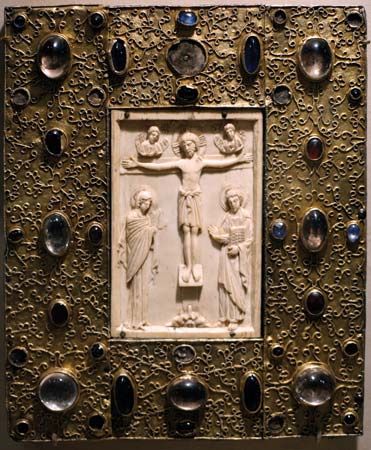

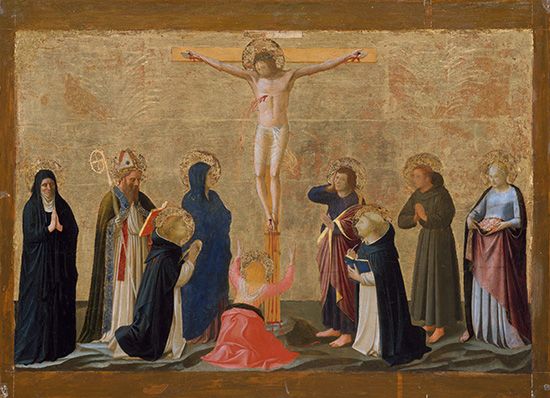

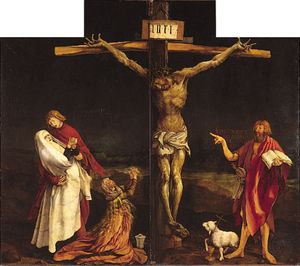

The representation of Christ on the cross has been an important subject of Western art since the early Middle Ages. Concerned primarily with simple symbolic affirmations of salvation and eternal life, and repelled by the ignominy of the punishment, the early Christians did not represent the Crucifixion realistically before the 5th century; instead, the event was symbolized first by a lamb and, after the official recognition of Christianity by the Roman state in the early 4th century, by a jewelled cross. By the 6th century, however, representations of the Crucifixion became numerous as a result of current church efforts to combat a heresy that Christ’s nature was not dual—human and divine—but simply divine and therefore invulnerable. These early Crucifixions were nevertheless triumphant images, showing Christ alive, with open eyes and no trace of suffering, victorious over death. In the 9th century, Byzantine art began to show a dead Christ, with closed eyes, reflecting current concern with the mystery of his death and the nature of the Incarnation. This version was adopted in the West in the 13th century with an ever-increasing emphasis on his suffering, in accordance with the mysticism of the period.

Parallel to this development in the representation of Christ himself was the growth of an increasingly complex iconography involving other elements traditionally included in the scene. The principal mourners, the Virgin Mary and St. John the Apostle, are frequently the only other figures included in the composition. In various expanded versions of the theme, however, there are several other pairs of figures, both historical and symbolic, that traditionally appear to the right and left of the cross: the two thieves, one repentant, who were crucified with Christ; the centurion who pierced Christ’s side with a lance (and afterward acknowledged him to be the Son of God) and the soldier who offered him vinegar on a sponge; small personifications of the Sun and Moon, which were eclipsed at the Crucifixion; and allegorical figures of the church and the synagogue. Other figures might include the soldiers who cast lots for Christ’s garments and St. Mary Magdalene.

With the growth of devotional art at the end of the Middle Ages, depictions of the Crucifixion became vehicles for the portrayal of Christ’s sufferings; calculated to inspire piety in the viewer, this spectacle became the main concern of artists, who often depicted the scene with gruesome realism and sometimes included the horror of a mass of jeering spectators. Some of the Crucifixions from this period include the figure of St. John the Baptist, pointing to Christ and his sacrifice as he had earlier heralded his coming. Renaissance art restored a calm idealization to the scene, however, which was preserved, with a more overt expression of emotion, in the Baroque period. Like most of Christian religious art, the theme of the Crucifixion suffered a decline after the 17th century; some 20th-century artists, however, created highly individual interpretations of the subject.