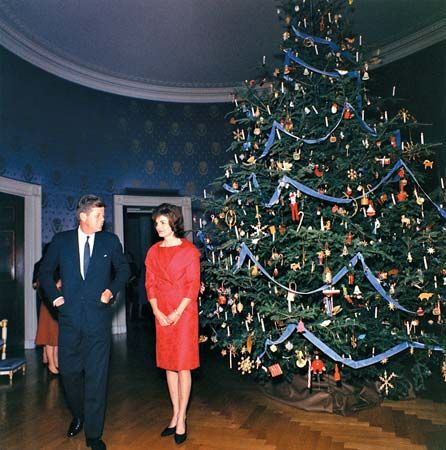

first lady

first lady, wife of the president of the United States.

Although the first lady’s role has never been codified or officially defined, she figures prominently in the political and social life of the nation. Representative of her husband on official and ceremonial occasions both at home and abroad, the first lady is closely watched for some hint of her husband’s thinking and for a clue to his future actions. Although unpaid and unelected, her prominence provides her a platform from which to influence behaviour and opinion, and popular first ladies have served as models for how American women should dress, speak, and cut their hair. Some first ladies have used their influence to affect legislation on important matters such as temperance reform, housing improvement, and women’s rights. Although the wife of the president of the United States played a public role from the founding of the republic, the title first lady did not come into general use until much later, near the end of the 19th century. By the end of the 20th century, the title had been absorbed into other languages and was often used, without translation, for the wife of the nation’s leader—even in countries where the leader’s consort received far less attention and exerted much less influence than in the United States.

The early years

Because the framers of the Constitution left the chief executive considerable latitude in choosing advisers, he was able to seek counsel from a wide variety of friends and family, including his wife. The first president made decisions that highlighted the consort’s role. When Martha Washington (first lady from 1789 to 1797) joined President George Washington in New York City a month after his April 1789 inauguration, she arrived on a conspicuous barge and was greeted as a public hero. The president had already arranged to combine his office and residence in one building, thus providing her with ample opportunity to receive his callers and participate in official functions. Although she refrained from taking a stand on important issues, she was carefully watched and widely hailed as “Lady Washington.”

Abigail Adams (1797–1801), the wife of John Adams, enlarged what had been primarily a social role. She took an active part in the debate over the development of political parties, and she sometimes pointed out to her husband people she considered his enemies. Although she did not disdain the household management role that her predecessor had played (she oversaw the initial move to the new White House in Washington, D.C., in November 1800), critics focused on the political counsel she gave her husband, and some referred to her sarcastically as “Mrs. President.”

Because Thomas Jefferson (1801–09) was a widower during his presidency, he often turned to the wife of Secretary of State James Madison to serve as hostess. Thus Dolley Madison had ample time (two Jefferson administrations and her husband’s two terms, 1809–17) to leave a strong mark. With the assistance of architect Benjamin Latrobe, she decorated the president’s residence elegantly and entertained frequently. Her egalitarian mix of guests increased her popularity. During the British assault on the White House in August 1814, near the end of the War of 1812, she provided for the rescue of some of the residence’s first acquisitions, which endeared her to many Americans and solidified the role of the president’s wife as overseer of the nation’s most famous home.

Elizabeth Monroe (1817–25), the wife of James Monroe, appealed to elitists who insisted that the presidential family should illustrate “the very best” of American society, but she had few supporters among those who were more egalitarian. Although she helped her husband select furnishings for the presidential mansion, newly rebuilt after the British assault in 1814 (this furniture became prized possessions of later tenants), she entertained much less than Dolley Madison, and Washingtonians reacted by boycotting some of her parties. Louisa Adams (1825–29), the wife of John Quincy Adams, struggled with the same problem her predecessor had faced: how to deal with the tension already evident in American culture concerning whether the president’s family should mix freely and live simply or reside in luxury and be revered from afar.

1829 to 1901

The presidential candidacy of Andrew Jackson illustrated how important the role of the president’s wife could be. Rachel Jackson did not live to see her husband inaugurated, but earlier she had been attacked by the press, with one newspaper questioning whether she was qualified to serve “at the head of the female society of the United States.”

By 1829 the outline for the job of president’s wife was clear: hostess and social leader, keeper of the presidential residence, and role model for American women. When the president respected his wife’s opinion (as John Adams did), she could also function as political counsel and strategist.

Between 1829 and 1900 many presidents’ wives—such as Margaret Taylor (1849–50), who was chronically ill, and Jane Pierce (1853–57), whose son had been killed in a train accident—sought to avoid public attention by withdrawing behind invalidism and personal grief. Their husbands, as well as other presidents who were widowers or bachelors, often turned over hostess duties to young female relatives (daughters, daughters-in-law, or nieces), whose youth gained them admirers and excused their lapses in etiquette or lack of sophistication. Among the handful of 19th-century presidential wives who did seek a public role, Sarah Polk (1845–49), the wife of James Polk, was well versed in the political issues of the day and was considered a major influence on her husband. Mary Todd Lincoln (1861–65), the wife of Abraham Lincoln, though insecure in a visible role, prevailed on her husband to grant favours to friends and hangers-on. Julia Grant (1869–77), the wife of Ulysses S. Grant, was an extravagant and popular hostess during the Gilded Age and was the first of the presidents’ wives to write an autobiography, though it was not published until 1975.

Before the Civil War the president’s wife had remained a local figure, little known outside the capital, but in the last third of the 19th century she began to receive national attention. Magazines carried articles about her and the presidential family. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, travel across the country became easier, and Lucy Hayes (1877–81), the wife of Rutherford B. Hayes, became the first president’s wife to travel from coast to coast. This exposure, plus her association with the popular temperance movement and her own simplicity in matters of dress and decoration, contributed to her immense popularity. After journalists hailed her as “first lady of the land,” the title entered common usage. Following the production of a popular play, First Lady, in 1911, the title became still more popular, and in 1934 it entered Merriam-Webster’s New International Dictionary.