gastronomy

- Related Topics:

- molecular gastronomy

- wine tasting

- grande cuisine

- chef

- kaiseki

What is gastronomy?

What is molecular gastronomy?

What are some staple foods in different gastronomic regions?

How did gastronomy develop in ancient Greece and Rome?

How did the Italian Renaissance influence French cuisine?

gastronomy, the art of selecting, preparing, serving, and enjoying fine food. Gastronomy is grounded in relationships between food, culture, and tradition. Through the ages gastronomy has proved to be a stronger cultural force among the peoples of the world than linguistic or other influences.

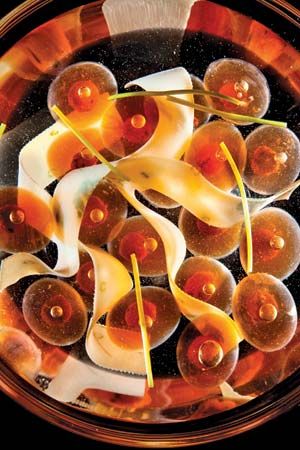

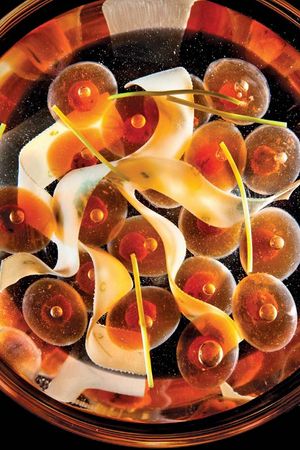

The new scientific discipline concerned with the physical and chemical transformations that occur during cooking is called molecular gastronomy. The new culinary style based on this new field is called molecular cuisine.

Today the world may be divided into definite gastronomic regions, areas where distinctive cuisines prevail and common culinary methods are practiced. Rice is the staple in most of Southeast Asia. The distinctive feature of the cooking of India and Indonesia is the generous and imaginative use of spices to lend an added zest to foods. Olive oil is the common denominator of the Mediterranean cuisines. Northern Europe and North America use a variety of cooking fats, among them butter, cream, lard, and goose and chicken fats, but the common gastronomic denominator throughout most of these lands is wheat. In Latin America corn (maize) is the staple and is used in a wide variety of forms.

This article covers the history of gastronomy from ancient civilizations through Greece and Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Italian Renaissance; the development of the great cuisines of France and of China; and the leading regional and national cuisines of the world.

History of gastronomy in the West

The first significant step toward the development of gastronomy was the use of fire by primitive humans to cook food, which gave rise to the first meals as families gathered around the fire to share the foods they had cooked. Prehistoric cave paintings such as those in Les Trois Frères in Ariège, in southern France, depict these early gastronomic events.

In the ancient civilizations of Assyria, Babylonia, Persia, and Egypt, the selection, preparation, service, and enjoyment of food were practiced on an elaborate scale. In the Book of Daniel the Bible relates the story of how Belshazzar, the king of the Chaldeans, “made a great feast to a thousand of his lords, and drank wine before the thousand.” He then commanded gold and silver vessels to be brought, and he and his wives, princes, and concubines drank wine and praised gods of gold, silver, brass, iron, wood, and stone.

Greece and Rome

In ancient Greece, the Athenians believed that mealtime afforded an opportunity to nourish the spirit as well as the body. They reclined on couches while eating and accompanied their repasts with music, poetry, and dancing. The Greeks provided a philosophical basis for good living, Epicureanism. It held that pleasure was the main purpose of life, but pleasure was not intended to imply the self-indulgence that it connotes today. The Epicureans believed that pleasure could best be achieved by practicing self-restraint and indulging as few desires as possible. Today the epicure is defined as one who is “endowed with sensitive and discriminating tastes in food and wine.”

The ancient Greeks practiced moderation in all things, but the Romans were known for their excesses. Ordinary citizens subsisted on barley or wheat porridge, fish, and ground pine nuts (edible pine seeds), but the Roman emperors and wealthy aristocrats gorged themselves on a staggering variety of foods. They staged lavish banquets where as many as 100 different kinds of fish were served, as well as mountainous quantities of beef, pork, veal, lamb, wild boar, venison, ostrich, duck, and peacock. They ordered ice and snow hauled down from the Alps to refrigerate their perishable foods, and they dispatched emissaries to outposts of the Roman Empire in search of exotic delicacies. Mushrooms were gathered in France, and the Roman author Juvenal, writing in the late first and early 2nd century ce, describes a dinner at his patron’s house where mullet from Corsica and lampreys from Sicily were served.

Yet, whereas the Romans placed great value on exotic delicacies, they were not gastronomes in the true sense of the word. The term implies a sensitivity and discrimination that they lacked. The unbridled appetites of the Roman emperors and nobles often carried them to wild extremes. The emperor Caligula drank pearls that had been dissolved in vinegar. Maximus reportedly consumed 60 pounds of meat in a day, and Albinus was alleged to have eaten 300 figs, 100 peaches, 10 melons, and vast quantities of other foods all at a single sitting. Lucullus was an immensely wealthy man who entertained so lavishly that his name became a symbol both for extravagance and for culinary excellence.

The vulgarity and ostentation of Roman banquets were satirized by Petronius in the Satyricon, written in the 1st century ce. A former slave named Trimalchio entertains at a gargantuan feast at which the guests are treated to one outlandish spectacle after the other. A donkey is brought in on a tray, encircled with silver dishes bearing dormice that have been dipped in honey. A huge sow is carved and live thrushes fly up from the platter. A chef cuts open the belly of a roast pig, and out pour blood sausages and blood puddings.

Middle Ages

Through most of the Middle Ages banquets and feasts were characterized by their crudity and extravagance. In more affluent households in Gaul, for example, huge quarters of beef, mutton, and pork were served up whole before the guests. Wild game was frequently served, including wild boar, hedgehog, roebuck, crane, heron, and peacock. Meats and other foods were cooked over fires on spits and in caldrons positioned close by the tables. Diners seated themselves on bundles of straw and gobbled huge quantities of food, sometimes drawing knives from sheaths in their sword scabbards to saw off huge chunks of meat.

The Frankish emperor Charlemagne introduced a touch of refinement. He decorated the walls of his banquet halls with ivy. Floors were strewn with flowers. Tables were laid with silver and gold utensils, but food was coarse, and menus offered little variety. The subtle seasonings and sauces that later were to characterize French cooking were still unknown. An insight into the relative crudeness of the French culinary art during the Middle Ages is provided by Le Viander (c. 1375), the first French cookbook of importance. It was written by Guillaume Tirel, more familiarly known as Taillevent, who served as chef to King Charles VI. Like the Romans, he used bread as the thickener for his sauces, instead of flour (which has been used for the past two centuries). He relied heavily on spices—such as ginger, cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg (a Moorish influence via Spain and Italy). His menus consisted mostly of soups, meats, and poultry, which were so heavily seasoned that the taste of the food was largely obscured. French cooking ultimately would be distinguished by the subtlety of its seasonings and sauces and by the imaginative blend of textures and flavours. But in Taillevent’s day the principal object of cooking was to disguise the flavour of the food (which, because of the lack of refrigeration, frequently was tainted) rather than to complement it.

The Italian Renaissance

The turning point in the development of gastronomic excellence was the Italian Renaissance. By the beginning of the 15th century wealthy merchants in Italy were dining in elegant style. In place of the crude slabs of meat served elsewhere, they savoured delicacies such as mushrooms, garlic, truffles, and tournedos (thick slices of beef fillets) and pasta dishes such as lasagne or ravioli. In wealthier households such delicacies were served in sumptuous style.

Development of French grande cuisine

The Italian influence on France

Italy has been called the mother of the Western cuisines, and perhaps its greatest contribution was its influence on France. The crucial event was the arrival of Catherine de Médici in France in the 16th century. The great-granddaughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Catherine married the young man who later was to become Henry II of France. She brought with her a retinue of Florentine cooks who were schooled in the subtleties of Renaissance cooking—in preparing such elegant dishes as aspics, sweetbreads, artichoke hearts, truffles, liver crépinettes, quenelles of poultry, macaroons, ice cream, and zabagliones. Catherine also introduced a new elegance and refinement to the French table. Although, during Charlemagne’s reign, ladies had been admitted to the royal table on special occasions, it was during Catherine’s regime that this became the rule and not the exception. Tables were decorated with silver objects fashioned by Benvenuto Cellini. Guests sipped wine from fine Venetian crystal and ate off beautiful glazed dishes. An observer reported that

the Court of Catherine de’ Médici was a veritable earthly paradise and a school for all the chivalry and flower of France. Ladies shone there like stars in the sky on a fine night.

Catherine’s cousin, Marie de Médicis, who married Henry IV of France, also advanced the culinary arts. An important new cookbook appeared in her time. It was called Le Cuisinier françois (1652) and was written by La Varenne, an outstanding chef, who is believed to have learned to cook in Marie de Médicis’ kitchens. La Varenne’s cookbook was the first to present recipes in alphabetical order, and the book included the first instructions for vegetable cooking. By now spices were no longer used to disguise the taste of food. Truffles and mushrooms provided subtle accents for meats, and roasts were served in their own juices to retain their flavours. A basic point of French gastronomy was established; the purpose of cooking and of using seasoning and spices was to bring out the natural flavours of foods—to enhance rather than disguise their flavour. In keeping with this important principle, La Varenne cooked fish in a fumet, or fish stock made with the cooked trimmings (head, tail, and bones). The heavy sauces using bread as a thickener were discarded in favour of the roux, which is made of flour and butter or another animal fat.

Contributions of the Sun King

La Varenne’s cookbook was a gastronomic landmark, but a long time was to pass before the French cuisine would achieve its modern forms. In pre-Revolutionary France, extravagance and ostentation were the hallmarks of gastronomy. Perhaps the most extravagant Frenchman of the time was the Sun King, Louis XIV, who, with members and guests of his court, wined and dined in unparalleled splendour at his palace at Versailles. There the kitchens were some distance from the king’s quarters; the food was prepared by a staff of more than 300 people and was carried to the royal quarters by a procession headed by two archers, the lord steward, and other notables. As the cry “the king’s meat” proclaimed their progress, an assemblage laden with baskets of knives, forks, spoons, toothpicks, seasonings, and spices solemnly made their way to the king’s quarters. Before the king dined, tasters sampled the food to make certain it had not been poisoned. The king himself was such a prodigious eater that members of the court and other dignitaries considered it a privilege merely to stand by and watch him devour his food. His sister-in-law reported that at one meal he ate

four plates of different soups, an entire pheasant, a partridge, a large plateful of salad, mutton cut up in its juice with garlic, two good pieces of ham, a plateful of cakes, and fruits and jams.

Louis XIV is remembered principally for his extravagance, but he was genuinely interested in the culinary arts. He established a new protocol for the table; dishes were served in a definite order instead of being placed on the table all at once without any thought to complementary dishes. The fork came to be widely used in France during his reign, and the manufacture of fine French porcelain was begun. Louis himself hired a lawyer-agronomist, La Quintinie, to supervise the gardens at Versailles and was intensely interested in the fruits and vegetables—strawberries, asparagus, peas, and melons—that were grown there. He paid special honour to members of his kitchen staff, conferring the title of officer on his cooks.

Triumph of French grande cuisine

During the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI, culinary methods were refined and a new order and logic were introduced into the French cuisine. Brillat-Savarin noted that in the reign of Louis XV

there was generally established more orderliness of meals, more cleanliness and elegance, and those refinements of service, which having increased steadily to our own time….

By the time of the French Revolution the interest in the culinary arts had intensified to the point where Brillat-Savarin could report:

The ranks of every profession concerned with the sale or preparation of food, including cooks, caterers, confectioners, pastry cooks, provision merchants and the like, have multiplied in ever-increasing proportions…New Professions have arisen; that, for example, of the pastry cook—in his domain are biscuits, macaroons, fancy cakes, meringues…The art of preserving has also become a profession in itself, whereby we are enabled to enjoy, at all times of the year, things naturally peculiar to one or other season…French cookery has annexed dishes of foreign extraction…A wide variety of vessels, utensils and accessories of every sort has been invented, so that foreigners coming to Paris find many objects on the table the very names of which they know not, nor dare to ask their use.

The Revolution changed almost every aspect of French life: political, economic, social, and gastronomic as well. In pre-Revolutionary days the country’s leading chefs performed their art in wealthy aristocratic households. When the Revolution was over those who were not subjected to the guillotine and remained in the country found employment in restaurants. The restaurant became the principal arena for the development of French cuisine, and henceforth French gastronomy was to be carried forward by a succession of talented chefs, people whose culinary genius has not been matched in any other land. From the long roll of great French chefs, a select company have made a lasting contribution to gastronomy.

The great French chefs

The first, and in many ways the most important of all French chefs, was Marie-Antoine Carême, who has been called the Architect of the French Cuisine. As French novelist and gastronome Alexandre Dumas père related the story, Carême was born shortly before the Revolution, the 16th child of an impoverished stonemason; when he was only 11, his father took him to the gates of Paris one evening, fed him supper at a tavern, and abandoned him in the street. Fortunately for gastronomy, Carême found his way to an eating house, where he was put to work in the kitchen. Later he moved to a fine pastry shop where he learned not only to cook but also to read and draw.

Carême was an architect at heart. He liked to spend time strolling about Paris, admiring the great classic buildings, and he fell into the habit of visiting the Bibliothèque Royale, where he spent long hours studying prints and engravings of the great architectural masterpieces of Greece, Rome, and Egypt. He designed massive elaborate table decorations called pièces montées (“mounted pieces”) as an outlet for his passionate interest in architecture. In an age of Neoclassicism his tables were embellished with replicas of classic temples, rotundas, and bridges constructed with spun sugar, glue, wax, and pastry dough. Each of these objects was fashioned with an architect’s precision, for Carême considered confectionery to be “architecture’s main branch,” and he spent many months executing these designs, rendering every detail with great exactness.

Carême was employed by the French foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, who was not only a clever diplomat but a gastronome of distinction. Talleyrand believed that a fine table was the best setting for diplomatic maneuvering. Following his service with Talleyrand, Carême practiced his art for a succession of kings and nobles. He catered a series of feasts for Tsar Alexander of Russia, was chef de cuisine to England’s Prince Regent (who later became George IV), and finally was employed by Baroness Rothschild in Paris.

Today Carême’s monumental table displays seem ostentatious almost beyond belief, but he lived in an opulent age that was obsessed with classical architecture and literature. To appreciate him fully, one must put him in the context of his time. Before Carême, the French cuisine was largely a jumble of dishes; little concern was given to textures and flavours and compatibility of dishes. Carême brought a new logic to the cuisine. “I want order and taste,” he said. “A well displayed meal is enhanced one hundred percent in my eyes.” Every detail of his meals was planned and executed with the greatest of care. Colours were carefully matched, and textures and flavours carefully balanced. Even the table displays, mammoth as they were, were designed and carried out with an architect’s precision.

Carême’s voluminous cookbooks, L’Art de la cuisine au dix-neuvième siècle (1833) and Le Pâtissier royal parisien (1815), included hundreds of recipes, menus for every day in the year, a history of French cooking, sketches for Carême’s monumental pièces montées, instructions for garnishes, decorations, and tips on marketing and organizing the kitchen.

After Carême, the two men who probably had the greatest impact on French gastronomy and that of the world at large were Prosper Montagné and Georges-Auguste Escoffier. Montagné was one of the great French chefs of all time, and he achieved a secure place in gastronomic history by creating Larousse Gastronomique (1938), the basic encyclopaedia of French gastronomy. As a young man, while serving as an assistant chef at the Grand Hotel in Monte-Carlo, he came to the conclusion that all pièces montées, as well as superfluous garnitures and decorations, should be discarded. This was a drastic step, and Montagné’s call might have gone unheeded had it not been brought to the attention of Escoffier. Escoffier was unimpressed at first. But his friend and literary collaborator Philéas Gilbert (also an outstanding chef) persuaded him that Montagné was right. Escoffier became a zealot for culinary reform, insisting on refining and modifying nearly every aspect of the cuisine. He simplified food decorations, greatly shortened the menus, accelerated the service, and organized teams of cooks to divide and share tasks in order to prepare the food more expertly and efficiently.

All of this progress was greatly facilitated by the introduction of the Russian table service about 1860. Before then, the service à la française was used. Under that method the meal was divided into three sections or services. All of the dishes of each service were brought in from the kitchen and arrayed on the table at once. Then, when this service was finished, all of the dishes of the next service were brought in. The first service consisted of everything from soups to roasts, and hot dishes often cooled before they could be eaten. The second service comprised cold roasts and vegetables, and the third was the desserts. Under the Russian table service, which was popularized by the great chef Félix Urbain-Dubois, each guest was served each course individually, while the food was at its best.

Escoffier invented scores of new dishes. One was poularde Derby, roast chicken with rice, truffles, and foie gras stuffing, garnished with truffles and foie gras. Other better known Escoffier inventions were pêche Melba, a dessert made with peaches, and Melba toast, tributes to Australian soprano Nellie Melba.

In naming some of his culinary creations after friends and celebrities, Escoffier was following a well-established tradition. Tournedos Rossini, the tender slices of the heart of the fillet of beef, topped by foie gras and truffles, was named after the celebrated Italian composer. Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi and French actress Sarah Bernhardt were among those who were similarly honoured. Many famous dishes have taken their names from the chefs who invented them—sole Dugléré, for example, was named after the chef Adolphe Dugléré, who presided at the Café Anglais in Paris in the middle of the 19th century. French dishes have also been named after their dominant colours, such as carmen or cardinale, which refers to a pinkish-reddish hue. Great events have also given dishes their names: chicken Marengo, for example, was named after the battle in 1800 in which Napoleon defeated the Austrians. Escoffier created a cold dish called chicken Jeannette. It was named after a ship that was crushed by icebergs. Escoffier’s creation was stuffed breast of chicken, and, in honour of the ill-fated ship, he served it on top of a ship carved out of ice.

The grande cuisine (or haute cuisine) of France is the only structured and organized system of gastronomy in the world. Many dishes are interrelated, and their names contain clues as to their ingredients. For example, soups are broken down into consommés (clear soups), potages (thick soups), crèmes (cream soups), and veloutés (made with a white sauce). Within each of these categories there are sub-categories, depending upon the base used, the thickening agent, the garniture, the flavouring spice, herb, or alcohol, and other considerations.

Escoffier’s fame today rests mostly on the cookbooks he wrote—Le Livre des menus (1924), Ma Cuisine (1934), and Le Guide culinaire (1921), written in collaboration with Gilbert—in which he codified the French cuisine in its modern form, setting down thousands of menus and clarifying the principles of French gastronomy. With the great hotel entrepreneur César Ritz, he established a string of the world’s most luxurious hostelries in Paris, Rome, Madrid, New York, Budapest, Montreal, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh.

In the late 1950s a group of young French chefs led by Paul Bocuse, Michel Guérard, the Troisgros brothers Jean and Pierre, and Alain Chapel invented a free-form style of cooking (named nouvelle cuisine by the French restaurant critics Henri Gault and Christian Millau). Their style disregarded the codification of Escoffier and replaced it with a philosophy rather than a structured system of rules, creating not a school but an anti-school, in reaction to the French grande cuisine. The basic characteristics of nouvelle cuisine included the replacement of the thickening of sauces with reductions of stocks and cooking liquids; the serving of novel combinations in very small quantities artistically arranged on large plates; a return to the importance of purchasing of food; and infinite attention to texture and detail.

At its best, nouvelle cuisine produced dishes that avoided rich sauces and lengthy cooking times, and its creative and inventive practitioners aroused interest and excitement in gastronomy generally and in restaurants specifically. One of its most important results has been the recognition of the chef as a creative artist.

Use of wines and sauces

French gastronomy is distinguished not only by the genius of its chefs but also by well-established culinary practices. One of these practices is the use of fine wines, such as those produced in Bordeaux and Burgundy, as accompaniments to good food. The proper choice of wines—according to vintages, vineyards, shippers—is an indispensable part of French gastronomy.

In the preparation of food, the hallmark of French gastronomy is the delicate sauces that are used to enhance the flavours and textures. Sauces are prepared with stocks, or fonds de cuisine, “the foundations of cooking.” These stocks are made by simmering meats, bones, poultry or fish trimmings, vegetables, and herbs in water to distill the essence of their flavours.

There are literally hundreds of French sauces, but among the more familiar ones are the families of white sauces, brown sauces, and tomato sauces, the mayonnaise family, and the hollandaise family. White sauces, which are served with poultry, fish, veal, or vegetables, are prepared by making a white roux, a mixture of butter and flour, which is cooked and stirred to smoothness. Béchamel sauce is prepared by adding milk and seasoning to this thickening agent. Sauce velouté is made by mixing a fish, poultry, or veal stock with the roux. A broad variety of sauces is derived from these basic white sauces. Sauce mornay is simply sauce béchamel with grated cheese and seasonings. Sauce suprême is béchamel with cream. Sauce normande is prepared by mixing a fish velouté with tarragon and white wine or vermouth.

Brown sauces, which are served with red meats, chicken, turkey, veal, or game, are prepared by simmering a meat stock for many hours and then thickening it with a brown roux, a mixture of butter and flour cooked until it turns brown. Among the better known brown sauces are sauce ragout, which is flavoured with bone trimmings or giblets; sauce diable, which is seasoned with lots of pepper; sauce piquant, a brown sauce with pickles and capers, and sauce Robert, which is seasoned with mustard.

The hollandaise family is another important branch of French sauces. Hollandaise is closely related to mayonnaise. It is prepared by delicately flavouring warmed egg yolks with lemon juice and then carefully stirring in melted butter until the mixture achieves a creamy, yellow thickness. Sauce mousseline is made by adding whipped cream to hollandaise, while sauce béarnaise also has an egg and butter base with tarragon, shallots, wine, vinegar, and pepper. Sauce vin blanc is made by adding a white-wine fish stock to the basic hollandaise.