“Energy As A Tool And A Weapon” was the ominous title of a recent hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. With introductions from fossil fuel fanboy and West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin and a witness panel that included a senior vice president at Shell, the hearing presented an opportunity for fossil-fuel friendly politicians to give the industry a leg up. “I find it difficult to believe we would not be facing an energy crisis if we had maintained greater energy independence, including exporting significant amounts of liquefied natural gas,” said Mississippi Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith during the hearing.

For the fossil fuel industry, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and resulting spike in oil prices have given them an opportune PR moment to hammer home some of their key messages: that environmental policies from the Biden administration are hurting production and that the industry should be allowed free rein to produce as much oil as possible. But the realities of this current price spike are far more complicated—and they come after a decade when much of the industry actually struggled with poor financial performance due to overproduction.

“There’s never been a time when the divorce between hype and reality in oil and gas has been greater,” Clark Williams-Derry, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, told me.

I called Williams-Derry just a few days after President Biden announced that he would ban imports of Russian oil to the U.S., to talk over what’s actually happening with oil prices and how that relates to what the U.S. fossil fuel industry is saying. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Molly Taft, Earther: How would you explain what’s going on with oil prices to the average person filling up at the pump? We only get 8% of our oil imports from Russia, and we’re such a powerhouse fossil fuel producer—so why is a ban such a big deal, and why are prices so high?

Clark Williams-Derry: Biden’s Russian oil ban hasn’t affected supplies in the U.S. yet. There may be a cargo that’s been canceled, but it’s had relatively little short-term impact on U.S. supplies.

People are probably wondering, hey, the U.S. produces a lot of oil, why don’t we just use our oil? Why can’t we just replace Russia’s 8% with our 8%? It doesn’t work that way. We’re part of the global market. Oil produced in the U.S. can just go straight out to other countries. And that ties our prices to the global market.

By choosing to export oil, we’ve basically hitched the U.S. economy and gas prices to a global roller coaster ride that we have no control over. And oil prices are basically decided by a bunch of sweaty men in a mosh pit in the NYMEX trading floor.

Earther: That’s a great explanation.

Williams-Derry: It’s mostly white guys who are yelling at each other. Some of them represent buyers, some of them represent sellers. And they’re trying to make a deal. The buyers want to buy oil, and they have limits on what they want to pay. The sellers want to sell oil and they want to get as much as possible. So they’re all sort of yelling at each other, and they are making trades between willing buyers and sellers, and the price that they settle on is kind of the best price. That’s what we talk about when we talk about the spot prices.

Earther: Some folks may think—and this seems to be backed up by messaging from oil interests—that we don’t have enough oil, and that’s why prices are so high. And you’re saying that it’s more about the conversation about pricing, rather than the actual availability.

Williams-Derry: Right now, there does not appear to be any physical shortfall. But part of the reason there’s not a physical shortfall is that prices are higher and people are conserving more. It’s this massive, multi-directional causal network that affects prices: how much consumers are willing to spend, how much the economy is growing, how much supply is growing, how much demand is growing. All these signals get integrated into one thing called the price. On top of all that, there’s the physical flow of trade. Then there’s time, because they’re not just setting contracts for now, they’re setting contracts for the coming month, or the month after that, or the month after that. They’re looking not just at what’s happening now, but they’re looking at the future.

One of the things that happens in oil markets, when sweaty men are yelling at each other, is they’re thinking about the future. What are the risks coming up? One of the big risks coming up now is a supply disruption. Traders are thinking, what happens if Russia decides we’re not going to sell to Europe? Or Europe decides we’re not going to buy from Russia? What happens if a pipeline is blown up? What happens if there’s sabotage?

When there’s uncertainty about the future, what happens is the price rises today, because people are locking in their supplies now.

Earther: It reminds me of when everyone was buying toilet paper at the start of the pandemic.

Williams-Derry: Exactly. At the time, it wasn’t like toilet paper supplies were suddenly cut off. But there’s uncertainty about whether toilet paper would be there in two months, or whether you’d even be able to go to the store in two months. You buy all of everything you can now, right? In oil markets, it’s not just that you’re locking in supplies now, you’re paying money to lock in your supplies in the future.

Earther: Can you talk me through some of what the industry has been saying during this time? Especially the American Petroleum Institute [the industry’s lobbying arm]—they’ve been hammering on how we need to increase LNG exports, we need to build more terminals. Would those policies actually have an impact on the energy crisis we’re seeing now?

Williams-Derry: Basically, the oil industry is saying, we need more of everything. We need you to build pipelines, we need you to build LNG facilities. But there’s a timing issue. A significant ramp up is going to mean major supply chain issues, and it’s going to take them time just to get the rigs into the field. Once you start drilling, it’s three months, maybe six months, until the oil starts flowing.

Even if you decide today that you want to drill, you can’t get more oil out of the ground for another six to nine months, you can’t increase the pace at which we’re producing. There’s a mismatch there. If you’re talking about building an LNG terminal to supply Europe—start now, maybe you’re done in three years, maybe longer. At that point, you’re looking at today’s crisis in the rearview mirror.

And one of the things that’s going to happen between now and then is that Europe is going to massively reduce its consumption of natural gas. They’re going to replace some of the Russian gas supply with supplies from Norway, some of it from Azerbaijan, some of it from global LNG supplies. But there’s a limited pot of global LNG. It’s not like you can just sort of turn on factories that don’t exist. Most of them are running at full capacity right now, or close to it, because prices are high, and why wouldn’t you? So all the available capacity is being spoken for, there’s gonna be a little bit of new incremental capacity from U.S. LNG terminals that are coming online right now.

This is all at a time when Europe has been running hard to conserve energy, insulate, install heat pumps, more renewables—everything they can do to reduce their consumption of gas, as well as replace supplies of gas.

The [International Energy Agency] came out [on March 3] with this new bold plan to cut one-third of the EU’s gas imports by the end of the year. (Editor’s note: You can read that plan here.) That is crazy—it’s basically like reducing 10% of their supply. On [March 8], Europe comes out and says, a third, screw that—two-thirds of Russian gas is going to be gone from Europe by the end of the year.

The impossible quickly becomes the commonplace. It’s this rapid change where there’s a total reframing of energy in Europe. Renewables, conservation, and efficiency are not just about energy security, they’re about national security. They’ve got war on their doorstep, and one of the weapons of that war is energy. Let’s neutralize that weapon.

Earther: It seems like countries aren’t just interested in finding more oil, but in changing the conversation about energy altogether.

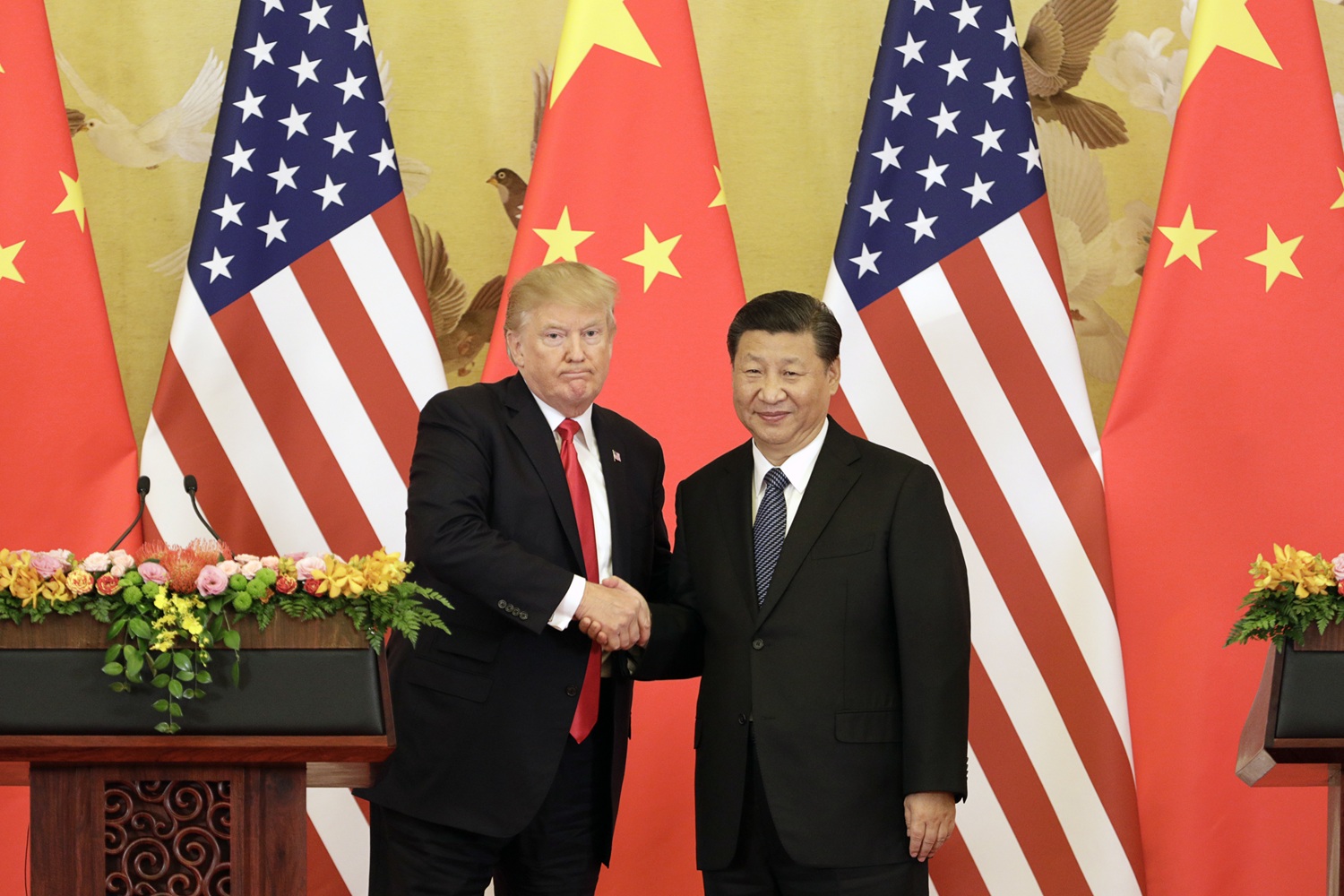

Williams-Derry: The energy transition is going to be happening as a matter of national security, and it’s going to be focused, I think, largely on Germany. High prices plus Germany’s example could accelerate the transition elsewhere in the world. This is why the industry right now is spinning so hard. It’s really somewhat afraid of the trends that have been unleashed by high prices. One of the key talking points from the industry is: “Lift the heavy hand of regulation from us and set us free. Under Trump we were doing great, under Biden—not so much.” None of that is true.

You look at stock prices during the 2010s, stock prices were collapsing. The industry was spending far more on drilling than they were spending on oil and gas. It was a financial shitshow. It was the worst place to put your money. Oil used to be 10%, 11%, 15% of the S&P 500, but as the fracking boom advanced, oil became 2% of the S&P 500.

Imagine you have a financial advisor, and this person says, I’ve got a great idea: take your money, split it into two piles, put one half under the mattress, let’s take the other pile into the backyard and set it on fire. That would have returned 20%, 30% more than betting on the oil and gas industry. Investing in oil and gas, through the beginning of covid when prices went negative, was like lighting your money on fire. And the industry was getting everything it wanted from Washington. The problem is that everything it wanted from Washington was more production, more production led to low prices, low prices led to a tidal wave of red ink.

Earther: So why is the industry seemingly pushing for more production now?

Williams-Derry: What they’re probably really pushing for is favors. Listen to [Pioneer Resources CEO] Scott Sheffield, listen to what [Occidental CEO] Vicki Hollub says. They are not planning on ramping up production much. They are very happy now, because they’ve finally discovered the secret. At the beginning of covid, when they stopped drilling, they started generating cash.

Earther: Because they stopped overproducing?

Williams-Derry: Yes. That did two things: They save on drilling costs—it’s expensive to drill, you’re not spending $7 million, $8 million on a well—and you’re not drilling so much, so the prices are rising. This is the moment the oil and gas industry has been waiting for. They don’t want to spoil the dividend party. They’re finally generating the cash their investors have expected them to do all along. They’re also very clear: even if we wanted to drill now, there are supply chain issues. In 2014, there were supply chain issues, and they solved them by throwing money at it. We need labor? Let’s pay a lot of money for labor, because we need to produce. Now, they don’t want to do that. They’re pretty happy with this. We’ve got a capital plan, we’re not going to produce.

Earther: So what is the industry doing in Washington, if not pushing for more production?

Williams-Derry: They are securing tax breaks, they’re securing favors. They want to secure more support for LNG exports in other parts of the world. That’s great for oil and gas companies; that’s bad for U.S. consumers. Just like we did with oil, we’re tying domestic gas prices to volatile international trends. We’re exporting LNG, we’re importing volatility and high prices. What they’re looking for is political favors that improve the finance of the industry without necessarily unleashing production. Right now, they’ve got all the cash they need. They’re printing money with every barrel of oil. They could sink that cash into more production, but they don’t want to.

The idea that Biden is squelching the oil industry—there’s very little substance to that. Biden conducted a big offshore oil lease sale. The administration has increased the rate of permits on federal lands. Basically, what the industry is complaining about is that Biden has said nasty things about it. I’ve seen claims, the Biden administration is creating a brain drain in the oil and gas industry—what are you talking about? The brain drain happened when the oil industry fired everybody during covid. You can’t blame Biden in 2021 for what happened in 2020.

Reality is kind of complicated, but it’s not that complicated. There’s never been a time when the divorce between hype and reality in oil and gas has been greater. The American Petroleum Institute is hoping that nobody remembers the industry just flushed hundreds of billions of dollars down the toilet, and that’s why they’re in trouble. It happened under Obama, it happened under Trump, and as far as I can tell, everything the industry wants is a recipe for bad results. It’s like giving kids nothing but dessert: It’s bad results, because it’s all sweets, no discipline. Covid and the great financial meltdown actually created the discipline the industry needs to generate money and create money, and that discipline equals: don’t drill much. Keep your drilling in check.

There’s a risk here, because prices are high now, but something happens in Russia, Ukraine, UAE boosts production, maybe Iran comes online—prices could come back down fast, too. They’re milking this moment now because they like the money. But also, if you invest now, you don’t start producing oil for six, nine months, maybe a year? At that point, today’s crisis is in the rearview mirror, and maybe prices have collapsed again. It’s complicated, but the industry has the lever. They can control things; the politics don’t.