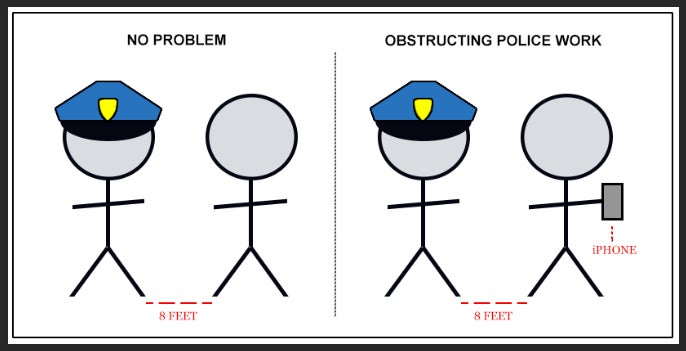

Arizona’s Republican governor, Doug Ducey, signed a bill into law this week that, with few exceptions, makes it a misdemeanor to stand within eight feet of a police officer and film them without their consent. The law, authored by a former police officer, has brought renewed attention to the legal fight over the right to film the police, a practice that gained special significance in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the nationwide protests that followed.

Under the new law, Arizona police officers are required to verbally warn would-be offenders that filming them within eight feet is a crime. A misdemeanor occurs if the camera holder continues to record the cop while failing to step back. The law covers not only onlookers drawn in by the sight of an arrest and subjects of police contact but also passengers in vehicles and people standing in their own homes, so long as the officer contends the filming is interfering with their work.

Those convicted under the law could face up to 30 days in jail.

The bill, in its various forms — a previous version had set the distance at 15 feet, but was curtailed out of constitutional concerns — faced stiff opposition from a range of First Amendment interests. In a February letter signed by the Committee to Protect Journalists and two dozen other news and photography organizations, it was described as not only violating the free speech and press clauses of the First Amendment, but the “clearly established right” to photograph and record police established by a majority of U.S. appeals courts.

While agreeing the right to film the police is not absolute in every circumstance, the letter’s sponsors highlighted key concerns with the Arizona law they said failed constitutional muster. Among them, that it nonsensically suggests the act of recording itself is what’s inherently dangerous. To wit: It is entirely possible to stand less than 8 feet from a police officer without interfering with their duties, yet it is impossible to do so while in possession of a recording device. (See diagram below.)

Filming is itself an act squarely protected by the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has long held that there’s no discernible line between speech and the creation of it; that to impair the latter is to imperil the former. Justice William Douglas, born only a few years after the invention of motion pictures, described the First Amendment as drawing “no distinction between the various methods of communicating ideas.”

The Supreme Court has so far declined to rule on whether filming the police is a protected constitutional right — ostensibly because in doing so, it could open individual police officers up to a barrage of civil claims — so Americans instead live by a patchwork of state laws and conflicting legal precedents. Some states, for instance, have tried to limit the ability to record police under wiretapping or anti-eavesdropping laws, drawing a technologically archaic distinction between video (legal) and audio (illegal, when police have an expectation of privacy).

Currently, all of the odd-numbered U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal (1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th) have recognized Americans’ right to film the police, with the 9th specifically having appellate jurisdiction over District of Arizona cases. Collectively, the precedents set by these courts are binding in a total of 25 states, in addition to Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin and Northern Mariana Islands.

The right to film police is often raised in the context of qualified immunity, a judicial doctrine designed to protect certain types of government officials —mostly police officers — from being held personally liable for monetary damages whenever they violate the law in the course of their duties. (The general concept being that lawsuits would be so abundant due to the nature of the work that no sane person would want the job, among other theoretical burdens on society.) The intertwining of these two issues has proven a barrier to establishing binding precedents that favor the right to film police in some jurisdictions.

A recent case in the Tenth Circuit became mired in this admixture.

In 2014, a Colorado man, Levi Frasier, was accosted by police after filming officers pummeling a man and the man’s pregnant girlfriend during a traffic stop. Eventually, one of the officers snatched Frasier’s recording device (a Samsung tablet) and attempted, failingly, to deleted the footage. Frasier sued the officers, arguing that their immunity did not cover what he viewed as an overt violation of his First Amendment rights. The panel of judges sided with the officers, saying the lower court should have granted them immunity the moment Frasier failed to point to any Supreme Court or Tenth Circuit decisions establishing his right to record them. Due to the way in which these arguments were presented, the court was able to fully sidestep ruling on whether Frasier had that right in the first place.

In November, the Supreme Court declined to hear Frasier’s case. Immediately after, Joe Biden’s Justice Department urged the Tenth Circuit to take the issue up once more — and this time, firmly establish the right. The argument for doing so now is that, basically, the time is long passed; that every circuit court to consider the issue has found the right to exist; and that First Amendment protections require “special force” when it comes to the public’s right to gather and disseminate information about its own government’s actions.

The courts have been careful, though, not to imply that this right is absolute. In 2017, the Tenth Circuit asserted the right is subject “reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions.” Before it, the First Circuit ruled, “Reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right to film may be imposed when the circumstances justify them.” The Supreme Court has found, for example, that journalists have no right to access a crime scene from which the general public is restricted.

In a 2012 case, the First Circuit elaborated on some of these “reasonable restrictions,” providing, as an example, “when the detained individual is armed.” Orders by police officers directed at people filming them may be constitutional it said, when police “reasonably conclude” that filming “is interfering, or is about to interfere,” with their duties.

At the same time, it suggested the amount of physical space between an officer and the person recording them could be relevant to whether filming is considered a “peaceful” act, versus one that’s “subject to limitation.” In the case of Simon Glik, a Massachusetts man arrested for filming police with his phone, it noted, for instance, that he did so only while maintaining a “comfortable remove.”

And while the same judges also noted that Gilk had not spoken to the police while recording them — describing this, too, as an example of how his filming was plainly “peaceful”’ — they appeared eager to quash the idea that police can impose restrictions on filming out of convenience, or because they’re simply annoyed. “In our society, police officers are expected to endure significant burdens caused by citizens’ exercise of their First Amendment rights,” the court said.

On the matter of whether lobbing insults at police is every American’s right, Justice William Brennan famously once wrote: “The freedom of individuals verbally to oppose or to challenge police action without thereby risking arrest is one of the principal characteristics by which we distinguish a free nation from a police state.”