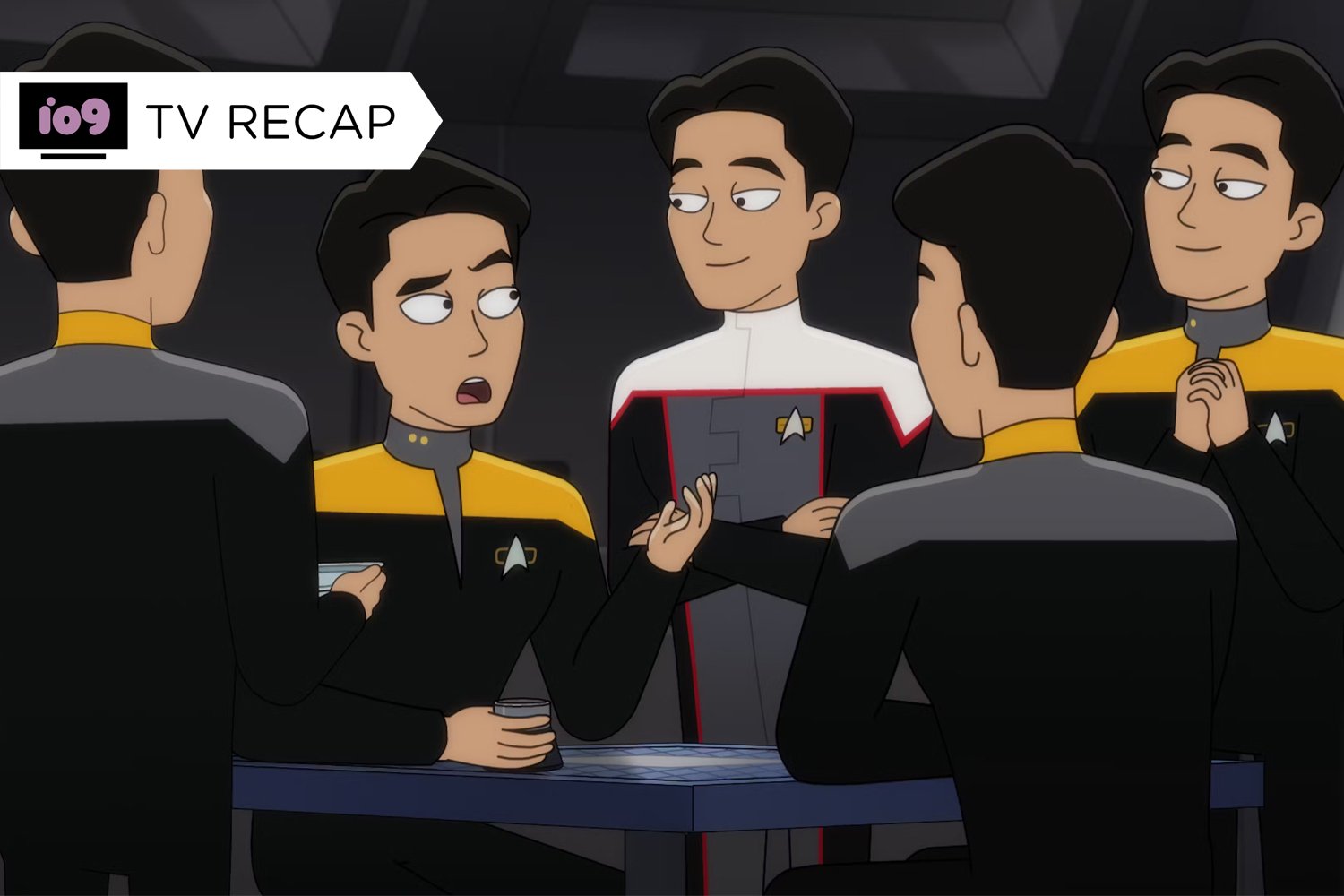

We all know that Star Trek gave us the iPad and countless other amazing devices — but the classic space adventure show also gave us some amazing breakthroughs in user interface design. Here’s a rundown of the lessons that Star Trek teaches about interaction design, from the new book Make it So: Interaction Design Lessons from Sci-Fi by Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel.

Chapter 3: Visual Interfaces

Case Study: Star Trek’s LCARS

One of the historically more significant shifts in sci-fi visual design occurred when Star Trek replaced controls based on mechanical, lighted buttons in the original TV series with the backlit touch panels in its first sequel series, Star Trek: The Next Generation. The new interface was striking not just for its visual distinctiveness but also for its comprehensiveness, extensibility, and influence.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, the reason for this change was the TV series’ budget: the creators simply didn’t have the funds to recreate displays and controls made from so many separate buttons across the vast surfaces of the Enterprise’s bridge. Production designer Michael Okuda and his team needed a much less expensive alternative. They looked to techniques such as those used in Logan’s Run nine years earlier, which featured sheets of plastic printed with graphics and backlit (at left).

Once Okuda’s team decided on this technique, it freed them from the cost and constraints of physical interfaces, opening up tremendous design opportunities. Whereas this technique was used only for displays in Logan’s Run, however, in Star Trek: The Next Generation it was used for controls as well, presaging touch-screen technology.

The result is the computer interface called LCARS (Library Computer Access and Retrieval System). It consists of a black background with a condensed sans serif typeface (SWISS 911 Ultra Compressed BT) used throughout. It features rounded-corner background graphics in flat, pastel blues, purples, and oranges with areas of brighter, higher intensity color for both graphics and text. These swooping background graphics form frames along a grid, providing a structure into which buttons, labels, informational diagrams, and video are placed. This graphic system supported a wide variety of applications, diagrams, controls, and Starfleet technologies. The LCARS interface was so durable that it was used consistently across three Star Trek TV series and four films. It even inspired two thematic transformations, to its “past” and its “future,” helping to reinforce the evolution of technology in this universe.

To differentiate the interface of the prequel, Enterprise, a different visual language was created for the touch-screen displays mixed with physical controls. These displays were less integrated into panels and surfaces than those seen in the LCARS interface. The Enterprise interface may have been inspired by the LCARS interface (and foreshadow it), but it isn’t technically part of it. The virtual portion of this interface used low-saturation color frames but buttons with more saturated colors, as well as a 2-D shading effect on the on-screen controls that mimicked physical buttons.

The Enterprise graphical language is almost entirely rectangular, and all data and controls are contained within closed, rectangular windows that do not overlap. There are very few round elements (though several of the window frames have a round “anchor” in the upper left corner), and a few rectangular buttons overlap their frames. These elements gave this series’ interfaces a distinct yet related appearance while introducing limited touchscreen capability.

A future variant of the LCARS interface comes in the fourth TV series, Star Trek: Voyager. In the “Relativity” episode, a Starfleet ship from the future uses a modified LCARS interface called TCARS (Temporal Computer Access and Retrieval System). The TCARS interface has notable differences, although its lineage is clear: the black background panels persist, as do the touch screens. But the framing graphics use curved shapes based on long ovals and a predominantly blue hue. Several buttons have curved sides, based on ovals and not circles. In some screens, round elements establish radial grids instead of the perpendicular grids seen in the LCARS interfaces. In addition to the flat frame graphics, several are given dimensionality with shading, although with a softer effect than in Enterprise.

These changes are enough to indicate the almost 200-year evolution of the TCARS interface from the fundamental elements of the LCARS interface. It serves to help audiences understand this leap in time without being confronted with something too unfamiliar.

In addition to the LCARS interface found in Starfleet ships in Star Trek, many of the same underlying elements are used in the interfaces of other races seen throughout the 24th century, across the series (Star Trek: The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager) as well as the films associated with them. The large touch-screen surfaces with black backgrounds persist, but the colors, frame shapes, layouts, and typefaces are usually changed to make them look somewhat distinct. The overall effect is to make them all feel current with each other, of similar technology, but specialized to the cultures that use them.

Lesson: Creative combinations of even common stylistic choices create a unique appearance

One of the most powerful ways to differentiate an interface, whether for sci-fi or real life, is to create an original color scheme, typographic treatment, and arrangement of displays and controls. This is no surprise to graphic or visual designers, but many clients (and directors) shy away from being original because they are leery of presenting their users or audiences with something too unfamiliar. However, as long as the visual elements are appropriate, don’t create confusion, and facilitate understanding, this is one of the best ways to create a unique or differentiated product brand or interface experience.

You can get 10% off the cover price of Make it So: Interaction Design Lessons from Sci-Fi, by Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel, by going to RosenfeldMedia.com and entering the code “io9”. The book is also available on Amazon and elsewhere.