Seemingly every corner of our world is now littered with plastics, and only a tiny percentage of it is ever recycled. To mitigate this, many companies are offering items labeled as “compostable” or “biodegradable” plastic—but as new research finds, those may be a misnomers.

A study published this week in Frontiers in Sustainability by researchers at University College London found that the majority of supposedly compostable plastics didn’t actually break down in home composting conditions.

The researchers solicited volunteers for a citizen science experiment called The Big Compost Experiment, encouraging people all over the UK to report how “compostable plastic” disintegrated over time. 1,648 people logged their home composting results with photos and written descriptions of how items did or did not change in the composting bin. In the end, 34% of the items disintegrated in the composting bins to the point where there were no traces left. 9% did not change at all, and 15% were intact and only showed some signs of discoloration after being in the composting bins. 31% of the items broke down to pieces larger than 2 millimeters but did not fully disintegrate. And 11% broke down to pieces smaller than 2 millimeters.

Danielle Purkiss, a study author, explained that the composting conditions were not standardized. Some of the participants composted bioplastic items for three months, some for half a year, and some for over a year. “We knew that there was an important variety across the UK. We wouldn’t have been able to recreate all of those practices in a lab condition,” she told Earther. “We were asking people to compost as they normally compost. Really tell us how these things actually perform in your real life.”

Purkiss pointed to past studies that may have composted bioplastics in labs or companies that have tested the compostability of their products in controlled environments. The best way to determine if the plastics they’ve manufactured will actually biodegrade is for the materials to be tested in a variety of composting environments. This is especially true if they’re expected to be composted by everyday consumers who do not have access to controlled composting facilities. Purkiss also noted that she and her colleagues expected more of the biodegradable- and compostable-labeled plastics to break down during the home experiments.

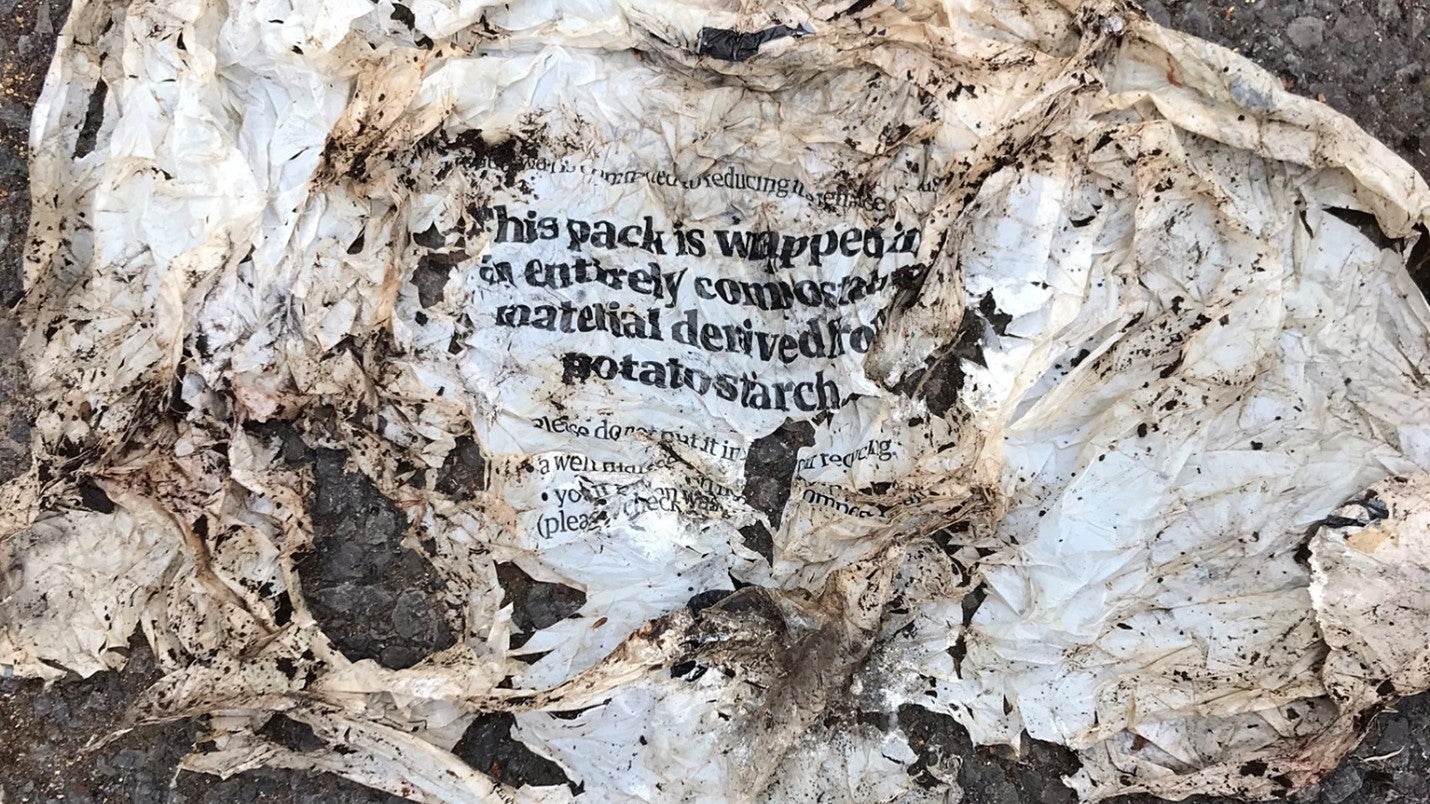

“We just assumed that things like films, the really thin compostable wrappers or films that you get around magazines, would be composting really quickly because they’re so thin,” she said. “Even the thinnest, flimsiest stuff is still persistent in people’s compost over a really long timeframe. So that’s really not good news for any other packaging types.”

Many of the experiment’s participants expressed that they used their compost in vegetable or flower gardens. Had the gardeners used the compost in their gardens, it would have contributed to microplastic pollution in soil—which lowers the health of the soil and resident organisms over time. Microplastic pollution has been alarming scientists and conservation groups for years. These plastic particles are on beaches, in Antarctic snow, and in the depths of the oceans. Earlier this year, scientists detected microplastics in human blood for the first time.

The team also found that the general public is often confused by the labels on supposedly compostable or biodegradable plastics. According to Purkiss, manufacturers need to clearly label the products and the best way to dispose of them. “We’re looking to try and steer the development of a different type of standard and certification process for these kinds of materials,” she said.