Solar energy has a dark side. Those gargantuan plants that sprawl out like deconstructed disco balls sacrifice valuable open space and put wildlife, and possibly human lives, at risk. A new study by Stanford researchers says that focusing our solar energy efforts in already-developed urban areas could yield more power—by collecting energy where we actually use it.

The idea of turning our cities into large-scale energy production centers doesn’t sound that radical, but it’s drastically different from the way power is delivered to our homes. For the most part, utility companies treat solar energy the same as other location-specific energy sources like hydroelectric plants or wind farms, so the majority of solar collection happens on dedicated land far, far away from cities.

Building the infrastructure systems to transport the energy from these rural areas into the city can end up costing almost as much as the plants themselves and cause the same level of environmental disturbance all the way back to town. And then you have to use energy to get it there. It doesn’t make much sense.

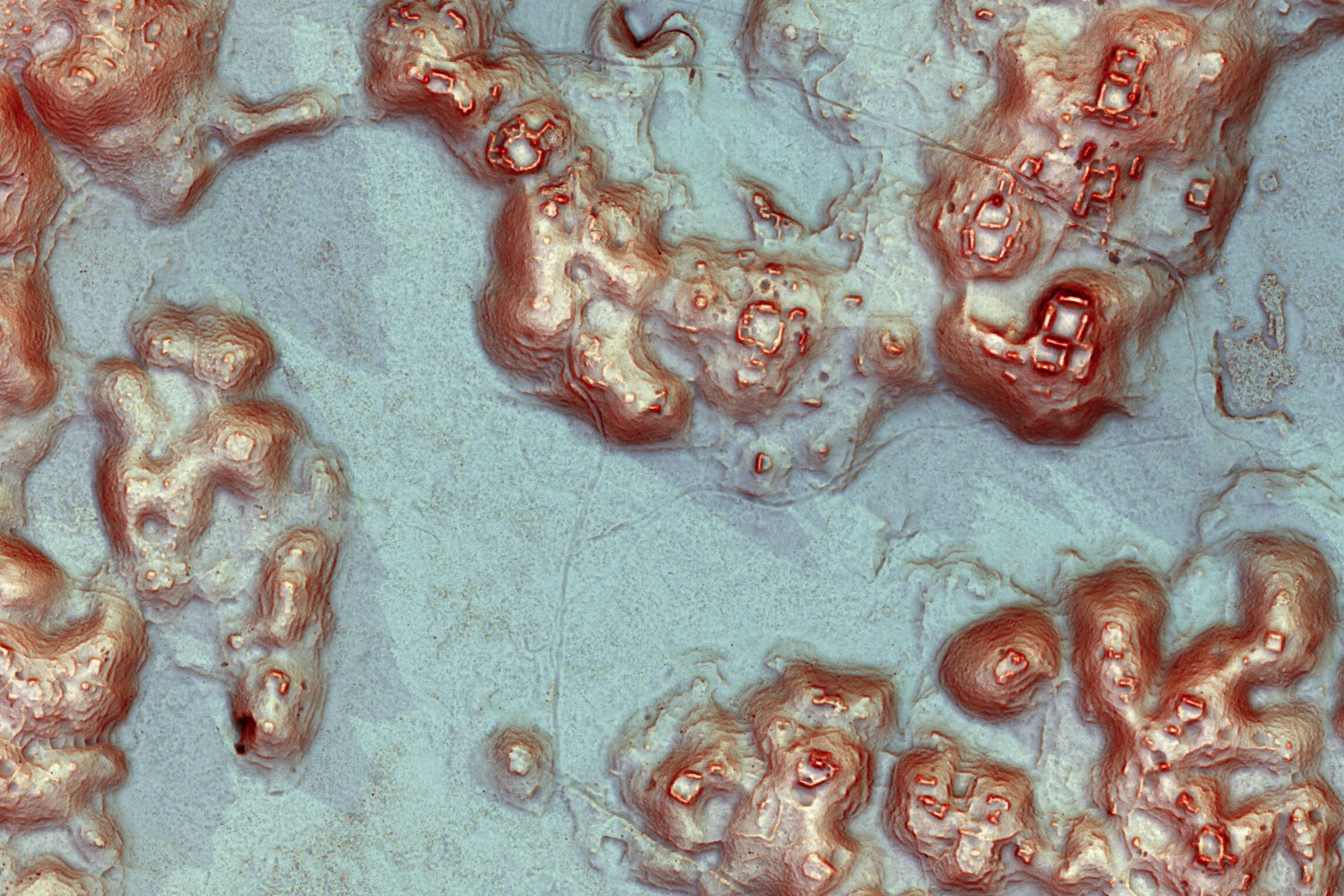

Ivanpah is the world’s largest solar plant, generating 392 megawatts (MW) of solar power on five square miles of desert near the California-Nevada border

The Stanford study, which was published in this month’s Nature Climate Change, turns this traditional utility model on its head. Looking at California, the current leader in solar energy production, researchers estimate that investing in a combination of both photovoltaic power (the typical solar panel) and concentrating solar power (how a plant like Ivanpah, the world’s largest, works) in cities alone would not only be more efficient, it would generate enough to supply the state with all its power needs—at least three times over.

It’s not too difficult to imagine how this might work. The types of urban surfaces we design are already naturally excellent at capturing solar energy, as evidenced by the heat island effect you’ll see on particularly sunny days. (And, of course, the large number of buildings which can melt things.) And there are plenty of blank flat surfaces which would be perfect for collecting solar energy. But even when it comes to designing these types of landscapes on purpose, the US is lagging. Some cities offer incentives to install photovoltaics on the exteriors of buildings or on places like the roofs of parking garages. But it hasn’t caught on, and this is all because American property owners are still at the mercy of utility companies.

Most solar panels are an ugly afterthought, which has stigmatized them in architecture. Here’s an example of a unique integration where the panels were installed vertically, by KoningEizenberg on an LA apartment building

What this study is proposing is part of a bigger idea of thinking of the city as a giant utility in itself, with buildings and public spaces that are specifically designed to capture solar energy and put it back to work on the spot—taking out the middle man. While this conjures up all sorts of thoughts of shimmery hyper-reflective sidewalks and bubbly biodomes, it doesn’t have to be that way—the solution might be simpler and more incremental than we think. Last summer at the Aspen Ideas Festival, I saw Nest founder Tony Fadell talk about his vision for converting our cities into solar-powered metropolises. It sounds reasonable, and awesome.

Consider this kind of solar energy collection at the smallest scale possible: A single-family home. You most likely purchase power from an company that may have some renewable energy sources, but likely gets all or most of its power from traditional coal-firing plants. The utility company usually decides what kind of energy you get, and they make choices based on how the utility company can make money. But if you had some kind of smart meter, perhaps similar to a Nest thermostat, you suddenly have all the information you need about the efficiency of your building, how much power you actually need, and what it will cost. You can decide which kind of energy makes the most sense to use. And according to Fadell, for four billion people on the planet, solar is easily the most plentiful and affordable source of power.

Nest Labs is has partnered with a utility company, NRG, to look at how homeowners can monitor their energy consumption and make decisions about it

Think of it as a version of energy cord-cutting. Your solar panel atop your house is the same off-the-grid dream from the 1970s, but it’s only due to emerging smart home technology that we can truly monitor our consumption and make educated decisions about it. Fadell related it to the dramatic changes in the telephone industry: It only took 20 years for the cell phone to kill the long distance call. We’ll no longer need the network of “long lines” from the utility companies. Soon we’ll all be masters of our own energy grids.

With proper regulatory changes and installation practices which could help drive cheaper, more efficient solar panel innovation for homeowners, the change could come swiftly. (Many European cities offer good models for how to quickly deploy solar installation at the neighborhood scale.) At his talk last summer, Fadell put it beautifully: “In ten years, you will be your own main generator, and you will be monetizing the energy value of your real estate.”

As the Stanford study’s authors rightly note, it’s not an all-or-nothing, urban-or-rural question when it comes to collecting solar energy. It’s important to remember there will always be a trade-off. But looking more closely at the opportunities in our actual backyards should be the priority. The sun shines in cities, too—so why not focus efforts on collecting it there? We shouldn’t need to plunder the desert to keep the lights on in our skyscrapers. [Climate Central]

Top image: Solar panels on the roof of the Vatican, Alessandra Tarantino/AP