The next hydrangea you grow could literally save your life. With the help of the Department of Defense, a biologist at the Colorado State University has taught plant proteins how to detect explosives.

Never let it be said that horticulture can’t fight terrorism.

Picture this at an airport, perhaps in as soon as four years: a terrorist rolls through the sliding doors of a terminal with a bomb packed into his luggage (or his underwear). All of a sudden, the leafy, verdant gardenscape ringing the gates goes white as a sheet. That’s the proteins inside the plants telling authorities that they’ve picked up the chemical trace of the guy’s arsenal.

It only took a small engineering nudge to deputize a plant’s natural, evolutionary self-defense mechanisms for threat detection. “Plants can’t run and hide,” says June Medford, the biologist who’s spent the last seven years figuring out how to deputize plants for counterterrorism. “If a bug comes by, it has to respond to it. And it already has the infrastructure to respond.”

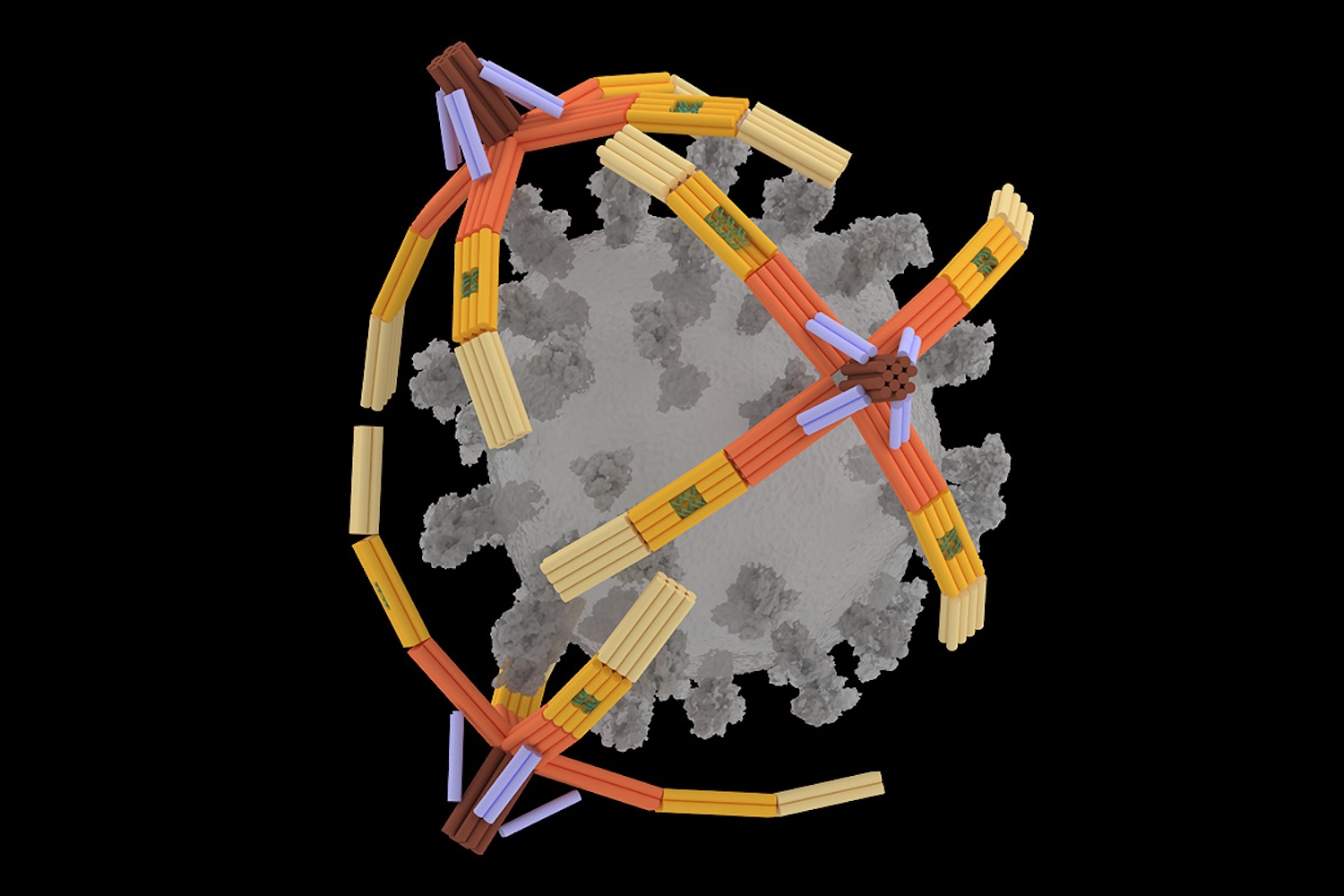

That would be the “receptor” proteins in its DNA, which respond naturally to threatening stimuli. If a bug chews on a leaf, for instance, the plant releases a series of chemical signals called terpenoids – “a cavalry call,” Medford says, that thickens the leaf cuticle in defense. Medford and her team designed a computer model to manipulate the receptors: basically, the model instructs the protein to react when coming in contact with chemicals found in explosives or common air or water pollutants.

“The computer program designs how the protein, which detects things, and explosive or environmental pollutant interact,” Medford explains to Danger Room. “We translate the language from the protein back to the DNA, and encode what we want in the DNA.” Her team published its findings today in the journal PLoS One.

It all started in 2003 with a Darpa program to grow circuitry. Back then, Medford heard about a program from the far-out Pentagon research arm called Biological Input/Output Systems, geared to produce “rational design and engineering of genetic regulatory circuits, signal transduction pathways, and metabolism.” The program was essentially a call for computer-designed receptors. “I was a plant biologist,” Medford recalls, “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if we put it all together, like Reese’s peanut butter and chocolate.'”

That led to a $2 billion grant from Darpa, with the Office of Naval Research kicking in another million. But by far the biggest benefactor to Medford’s research is the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which last year gave her a $7.9 million grant to get the bomb-sniffing ferns from the lab to the real world.

Right now, Medford estimates she’s three to four years out. Her labs have genetically-designed plants blanching white when they come into contact with TNT. But that’s in a research lab, where the amount of light is constant, “no wind, no rain, no bugs, no people dumping coffee.” Still, with the Department of Homeland Security unsure how to field non-intrusive technology for detecting bombs at public events, here’s a premium on sensors that double as a sweet-smelling garden; Medford says she’s “going back and forth” with DHS, but won’t disclose more than that.

One big problem: Medford probably thinks it’s not feasible to get the plants to react to ammonium nitrate, a common chemical used for homemade bombs in Afghanistan (and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing) since, after all, it’s found in fertilizer.

Eventually, Medford expects to bring the bomb-detecting plants to market through genetically modified seedlings. Whatever it costs, it’s got to be less than the $100,000 to $200,000 that a backscatter “junk scanner” can run. The reaction of the plants depends on the concentration of the chemical it comes into proximity with; Medford says her goal is to get her plants as sensitive as a dog’s nose.

And the best part? Because the proteins can live in any plant, there’s no specific vegetation that couldn’t become a sensor. Get ready for grow houses designing terror-fighting purple kush. That’s the kindest bud of all.

Photo: Noah Shachtman

Note: This article originally credited the University of Colorado for this research instead of the Colorado State University. This has been corrected.