Yesterday morning, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft slammed into the day side of Saturn, the brief flash of its vaporization marking the end of a 13-year mission. But it took people to turn this hunk of aluminum and silicon into an extension of our curiosity.

For the past three days, I’ve chatted with engineers and scientists at the wooden tables dotting Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s pedestrian mall, and in the sage-scented gardens surrounding Caltech. These are the people behind Cassini’s mission, who shepherded the spacecraft from concept to completion. They are the collective heart, brains and soul that transform its measurements into data. From twenty-seven-year mission veterans to new hires in the past few months, they all shared complex reactions of pride, exhaustion, and sadness when faced with Cassini’s Grand Finale.

“I’m wondering if my muse is disappearing,” Jonathan Lunine tells me as a documentary crew charges past us in the courtyard. He’s the interdisciplinary scientist coordinating the exploration of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. “Cassini will always be the touchstone for my career.” Shaking off his morose reflectiveness, he finds a silver lining to share. “I’m looking forward to spending more time engaged with the data than planning.”

Days before Cassini’s final plunge, I asked David Doody, who supervises real time operations, how he was feeling. “Dread,” he told me with with a laugh.“This fine mission is ending, sailing off into the unknown.”

Doody supervises realtime operations “where the rubber meets the road”—the human traffic directors for Cassini’s incoming data that shunt ones and zeros to their appropriate stations. He started working on Cassini in 1997, and the mission’s end has him reflective. But he won’t be resting long now the mission is over: “I’ve got documentation to do.”

Trina Rey is another long-time Cassini veteran who joined the team overnight in 1996 to help with “shake and bake” vibration and heat testing during spacecraft construction, and stuck around ever since.

“I’ve been calling into operations status meetings for twenty years,” she tells me. “The last meeting is on Tuesday.” The handkerchief she used to dab her eyes is Cassini-purple, perfectly coordinated with her official mission shirt.

“Every month or so, Cassini sends me this little burst of data. ‘Here Trina, here’s something you might not know…’,” she teases before sobering. “It’s going to take a while to get used to not having that.”

When I ask Cassini flight controller Joan Stupik how she is feeling, she turns it around on me. “I’m used to seeing how [Cassini] is feeling every day.” New to the mission, she was delighted to share excitement when scientists couldn’t wait to share images of Saturn’s wonky shepherd moons. For her, Friday morning was a bittersweet vigil, participating in the color commentary of Cassini’s final moments.

“I think I’m still in denial,” Carl Murray confides during a lunch break as across the solar system Cassini makes its final photographic tour of the Saturn system on Thursday. “We still have images coming down. We have a functional spacecraft. What could possibly go wrong?”

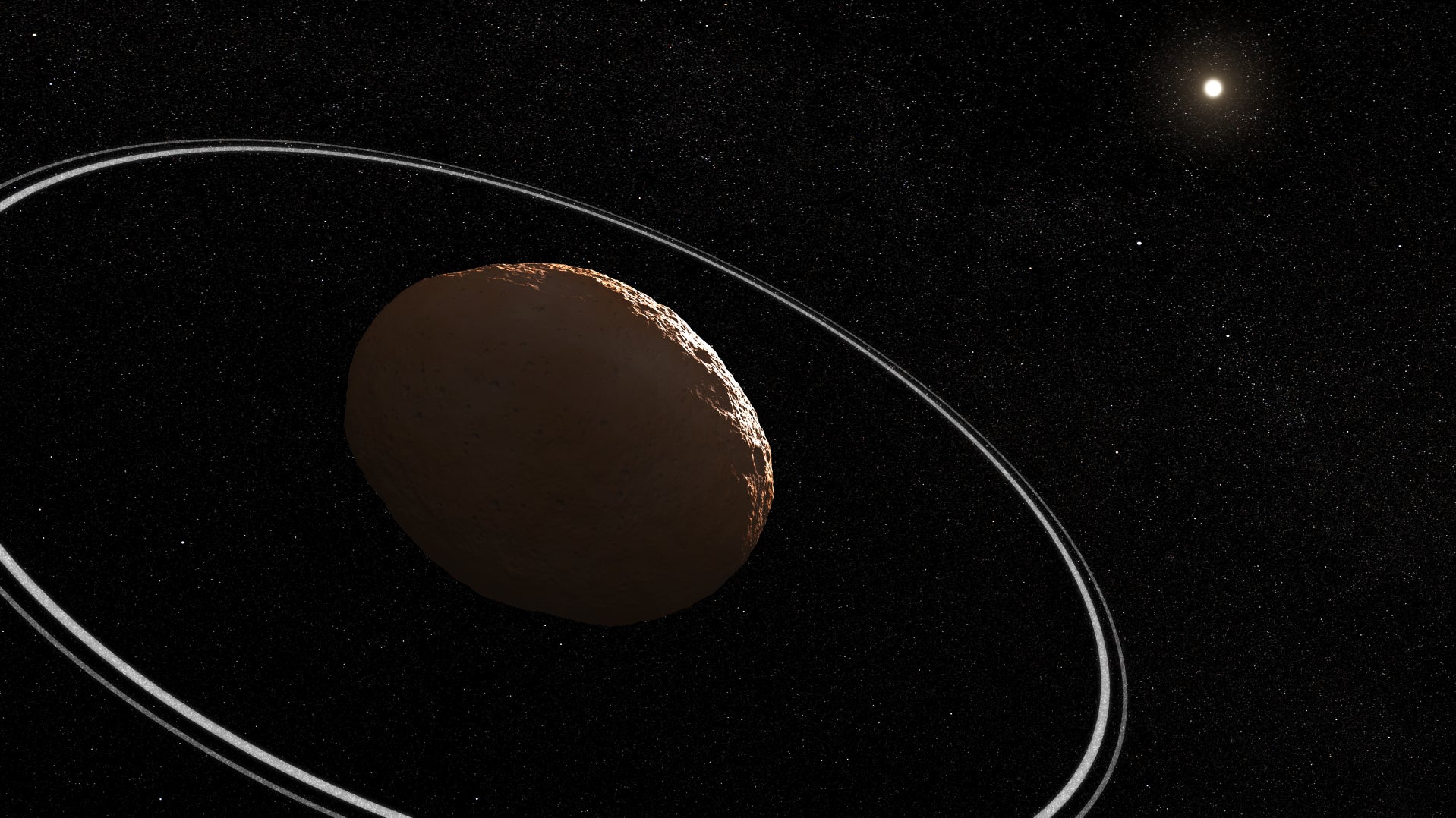

Murray applied to join Cassini at the start of the mission using astrometry to explore images by exposing them until objects are backdropped by starry skies. That’s how he found Peggy, a glitch in Saturn’s outer ring that’s yet to be fully explained. “Cassini has answered questions,” he tells me. “But like any good mission should, it has produced so many more questions that need to be answered.” A hint of a smile emerges as he contemplates the mysteries yet to be solved. “Maybe Monday is Day One of [answering them].”

After Cassini vaporizes in Saturn’s storms, its final radio signal lost forever, the uncertain mood shifts and solidifies. A moment of sadness, intensity of emotion overwhelming even those who thought themselves immune, then applause and finally celebration takes hold.

“How are you?” I ask Andrew Ingersoll, an atmospheric scientist with the team. “I’m very lucky to have been a part of this mission, and to have been alive in the Space Age,” he immediately responds. I soon learn of his career from Pioneer through Voyager to twenty-seven years working with Cassini, and how very excited he is to see how this deep-space craft fared at collecting an atmospheric sample for him to analyze. “Hydrogen and helium float up to the surface of Saturn,” he explains. “Anything that isn’t hydrogen or helium has to be ring rain coming down from above!”

I cross the auditorium to eavesdrop on John Casani, Cassini’s pre-launch project manager, and Charles Elachi, former director of overseeing operations at JPL and Cassini’s radar lead. “How are you feeling?” I ask in my now-habitual refrain. “I feel great!” Casani declares. “The spacecraft went out the way I hope to go out in my life: quickly!”

“And doing science to the end,” Elachi teases.

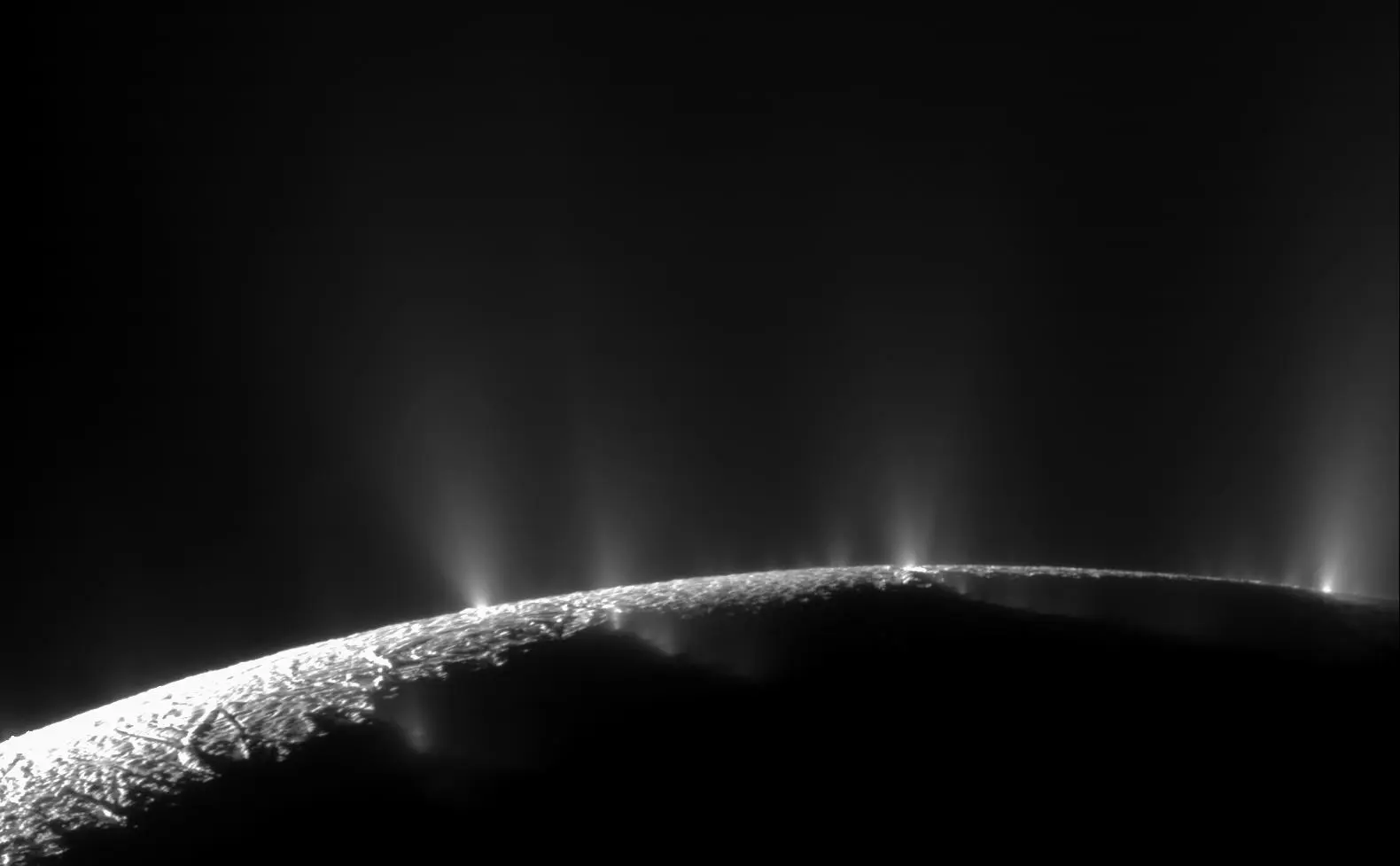

“For me it was just a piece of aluminum and silicon,” Casani says. “It’s just parts until engineers do something with it.” For all his pragmatism, he lights up when describing his favorite discoveries. “Enceladus,” he declares without hesitation. In its first year around Saturn, Cassini discovered that this icy moon harbored not only a liquid ocean water below its icy crust, but that it had geysers spewing that water into space.“There’s a little, tiny rock in space venting water. It’s incredible.” Elachi holds himself back from interjecting, trying to wait his turn to be interviewed.

“In my book, this is one of the greatest science missions this country has ever undertaken,” Elachi tells me. His top discovery is the lakes and seas of Titan. “Titan is like Earth, but the weather is all with liquid natural gas.”

I wander the auditorium, talking to any purple-shirted mission team member I can find. Chuck Kirby spent nineteen years of his thirty-year career on Cassini. “It’s bittersweet,” he tells me. But he’s excited about training for his new mission, NASA’s SMAP satellite monitoring soil moisture. “I’d like to spend the rest of my career fighting climate change.”

I spot one scientist in an orange shirt, yet bearing the same Cassini logo. Kareem Badaruddin is a tester for Cassini’s brain, dedicated to finding problems to fix before they emerged in the field. “How are you?” I ask. “Tired,” he says, but the longer we talk the more details emerge. He remembers coming to this same auditorium nearly twenty years ago to watch Cassini launch. His wife was very pregnant with their first child, and unimpressed when a hardware failure forced a launch scrub. They returned to bear witness as Cassini broke free of Earth’s bonds on October 15th, and their son was born nine days later.

“My son and Cassini came to adulthood together,” he tells me. “We got to Saturn when he was in first grade, discovered geysers on Enceladus when he was in second grade.”

Our early-morning gathering is an echo of an earlier time for Badaruddin. Cassini launched without an orbital insertion algorithm, the ability to use its reaction wheels, or the capacity to deploy the Huygen’s probe. For the six years and eight months the spacecraft flew past Earth, Venus, and Jupiter while cruising to Saturn, Badaruddin walked to JPL at 3:30am to start his workday early, cramming to build capacity before the spacecraft’s arrival at Saturn. “It’s dark and cold,” he tells me of early morning walks both past and present. “I saw three skunks this morning. I only saw one during all my walks before.”

Family members are here, too, reminders that the unrelenting demands of orbital dynamics stretch beyond awkward 3am press events to witness the spacecraft’s demise. Rosina Maize is proud of her husband Earl’s accomplishments as Cassini’s program manager. But she’s also written the mission timeline on her household calendar for years, turning down social plans for flybys and critical trajectory corrections.

“I can be alone on Christmas or invite all these European scientists to our home,” she says, recalling the timing of Cassini releasing its European Space Agency-led Huygens probe on December 24, 2004. In the aftermath of the Grand Finale, the Maizes will be adding a personal note to their celebration. “Yesterday was our anniversary,” she confides.