A scary situation is developing in the southern Atlantic Ocean, as iceberg A68a is now within striking distance of South Georgia island. Alarmed by the turn of events, a team of scientists is heading out to investigate the ways in which this gigantic iceberg might affect the local wildlife.

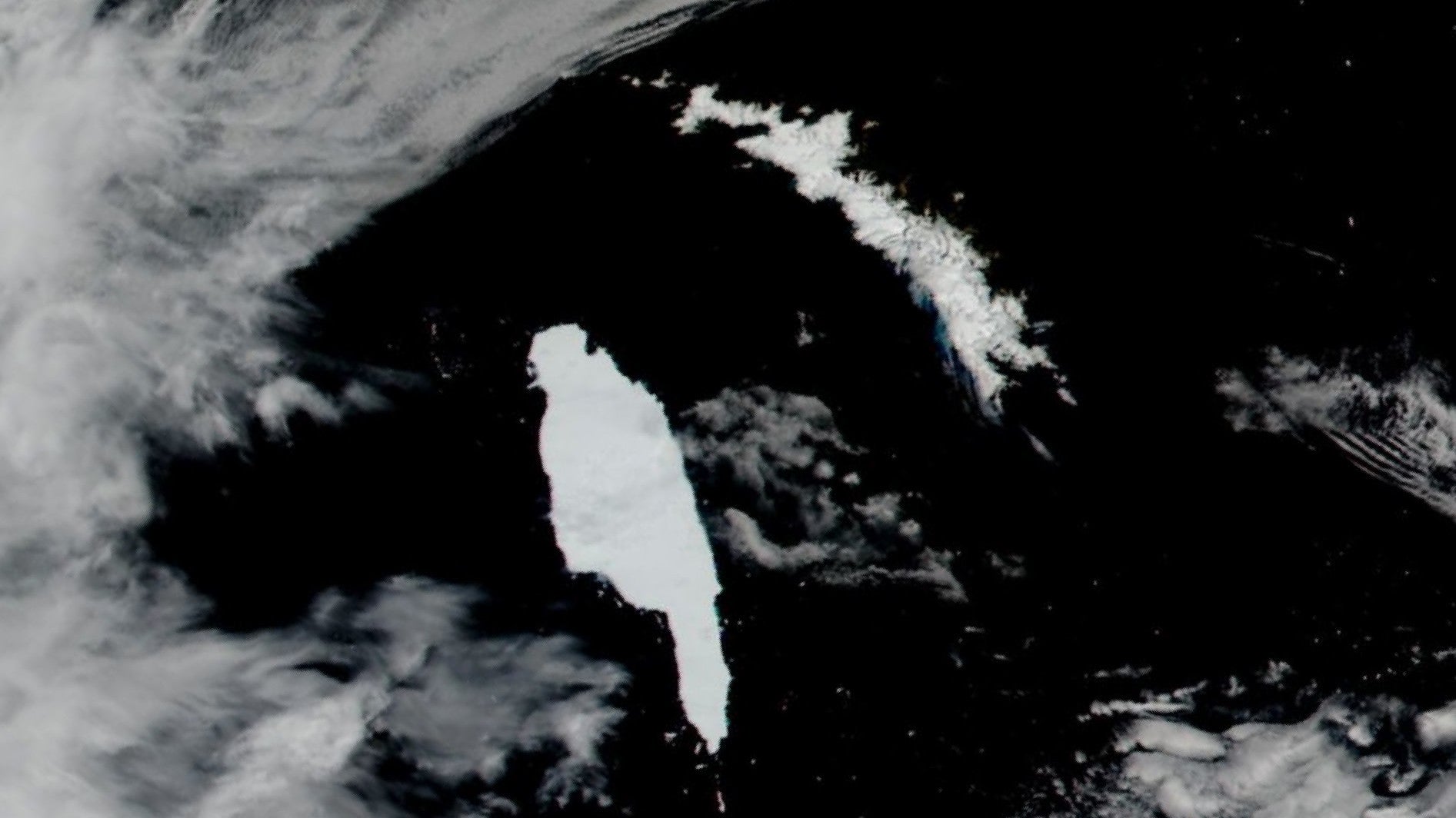

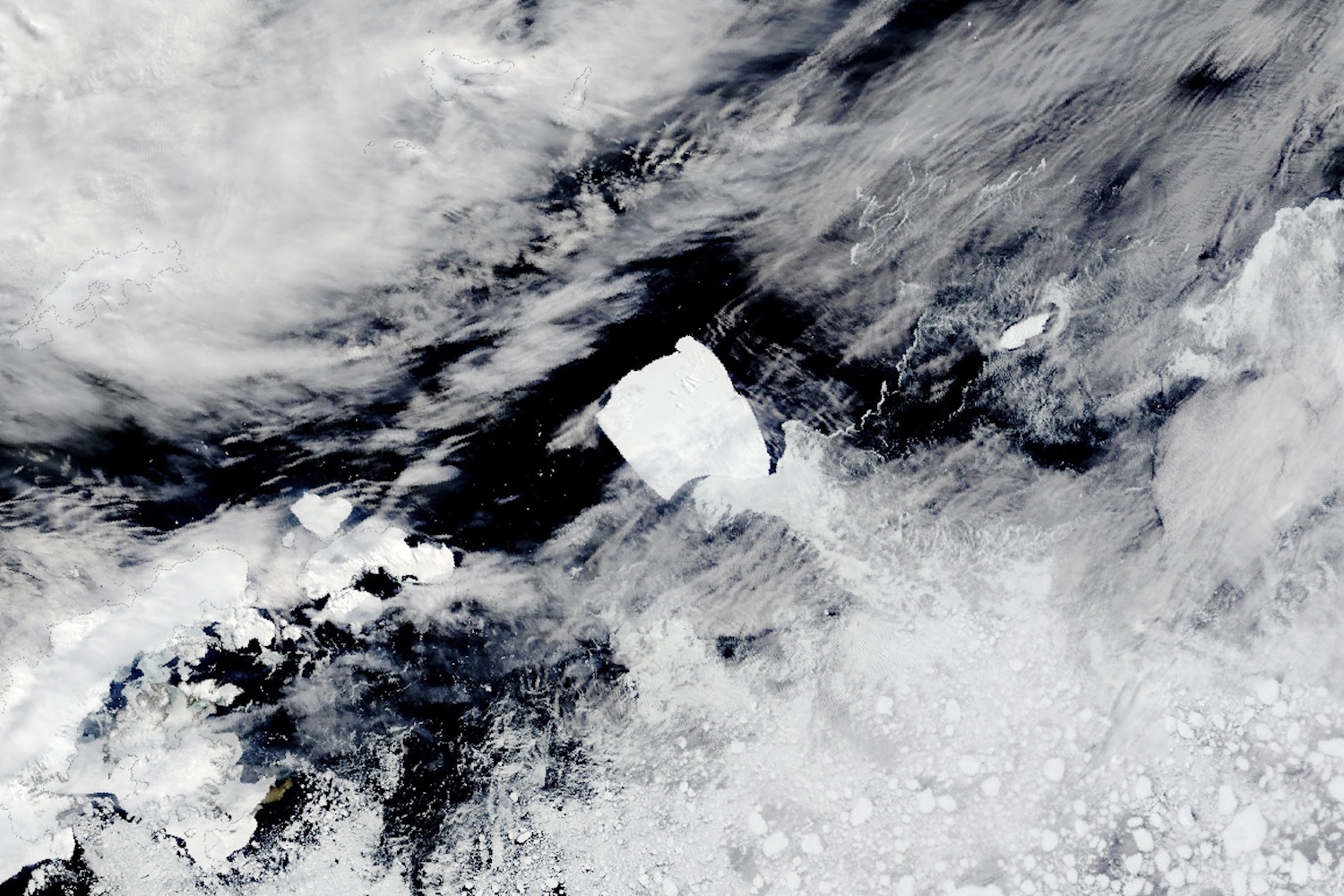

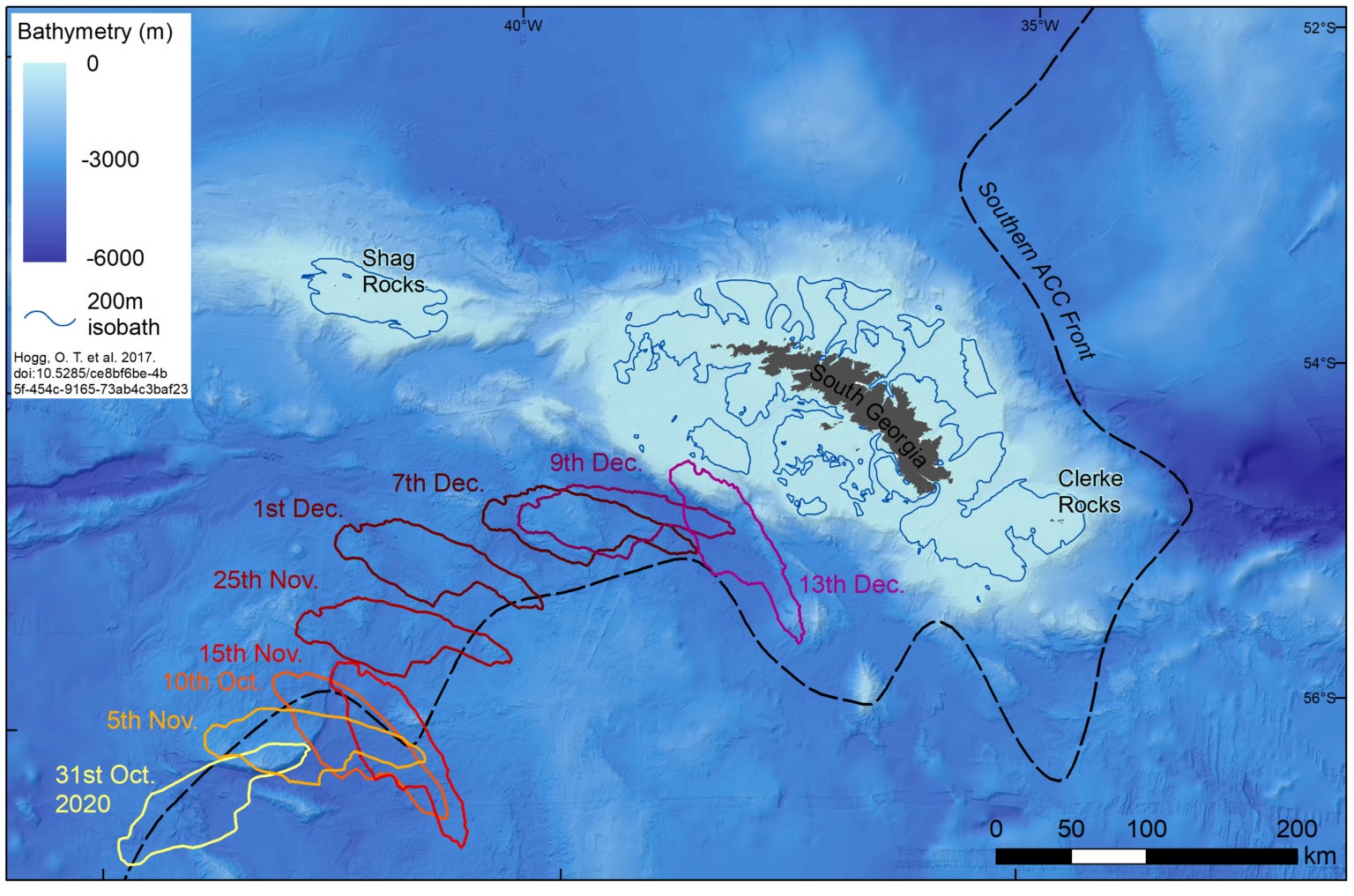

When we last reported on this story on November 27, things were looking up, as iceberg A68a appeared to be rotating and potentially drifting westward, away from South Georgia. Plenty has changed since then, with new satellite images showing the iceberg a mere 46 miles (75 km) southwest of the British Overseas Territory, which is more than 100 miles (160 km) closer than it was just three weeks ago.

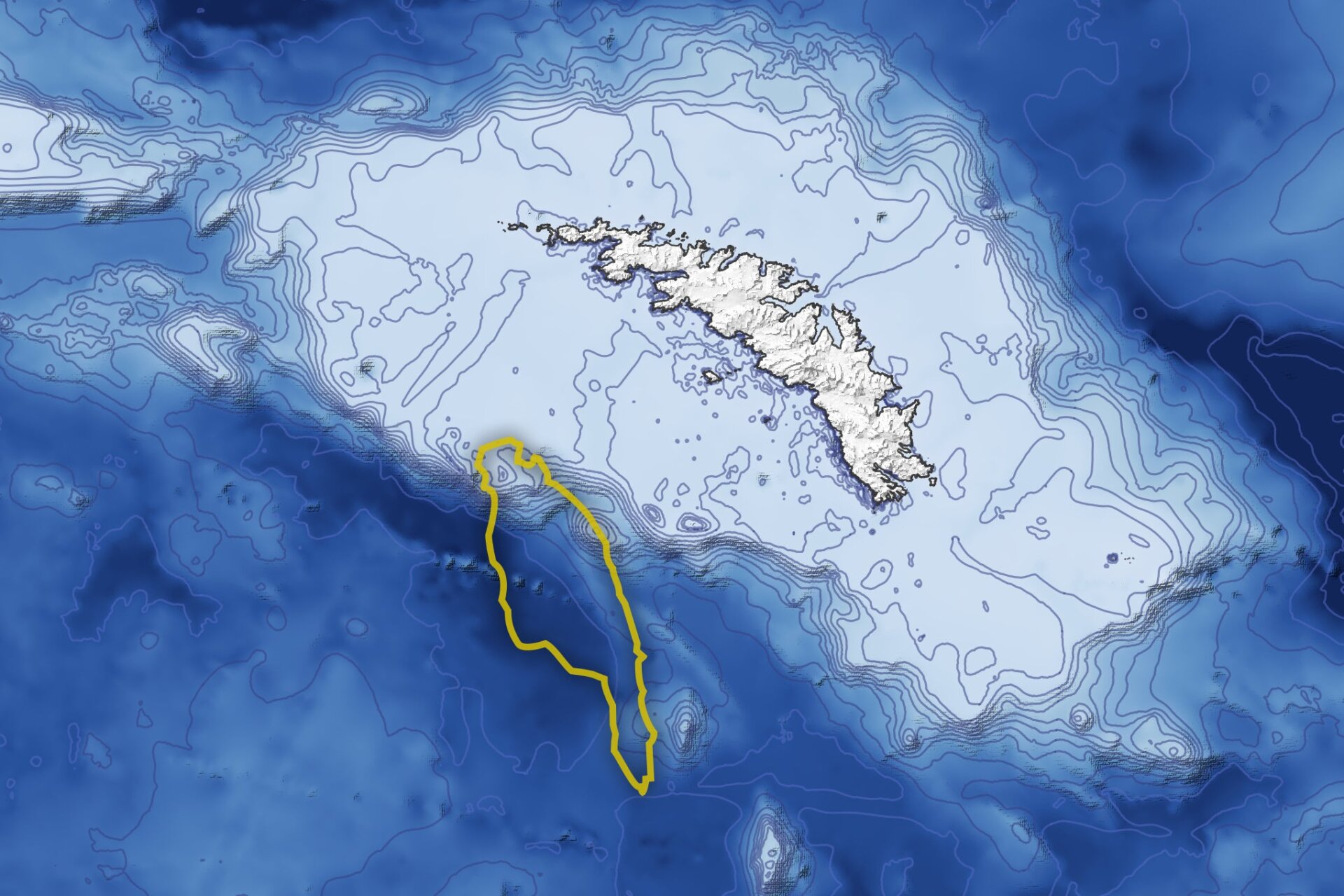

So close is the iceberg to South Georgia right now that portions of it may have already passed over or collided with the island’s shallow submarine shelf, as this topographic map (below) shows.

Indeed, the big fear is that A68a—currently the world’s largest iceberg—will scrape its way along the bottom of the seafloor and become lodged in place, possibly for years to come. Biologists worry about the effects this merger might have on the local wildlife, including penguins’ ability to source food.

“The iceberg is going to cause devastation to the sea floor by scouring the seabed communities of sponges, brittle stars, worms and sea-urchins, so decreasing biodiversity. These communities help store large amounts of carbon in their body tissue and surrounding sediment,” explained British Antarctic Survey ecologist Geraint Tarling in a statement. “Destruction by the iceberg will release this stored carbon back into the water and, potentially, the atmosphere, which would be a further negative impact.”

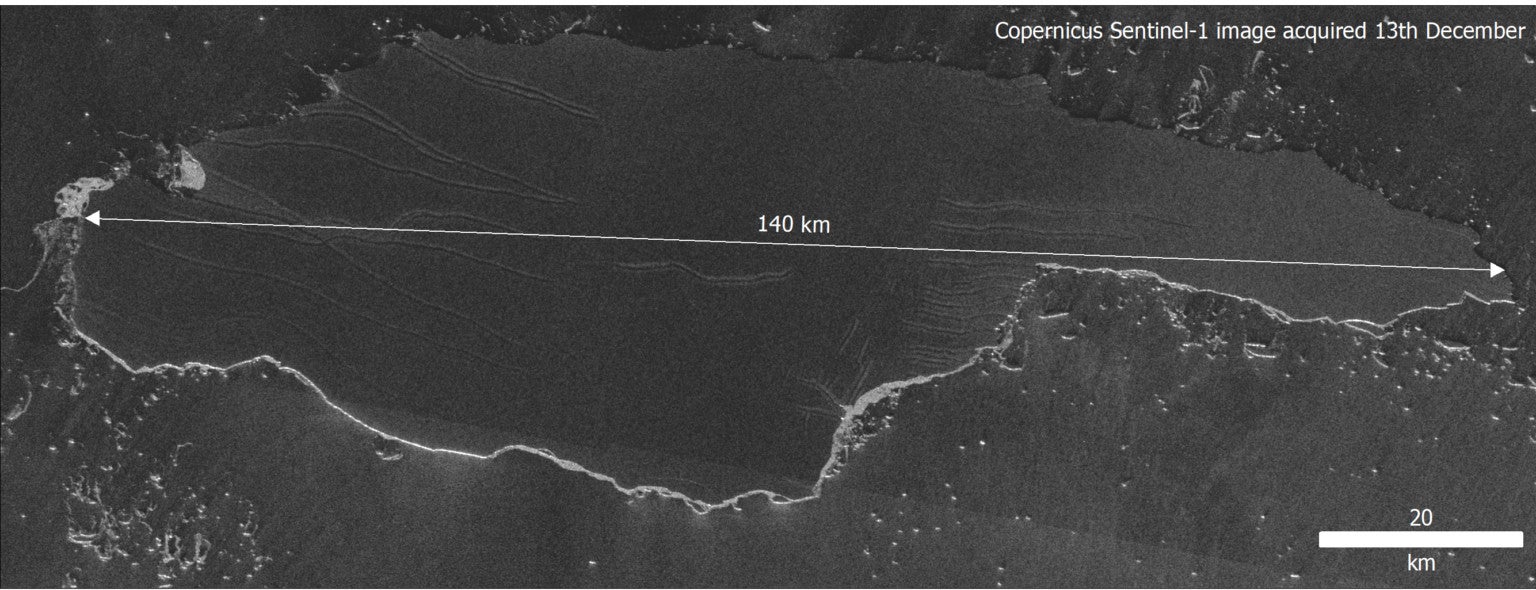

A68a broke free from Antarctica’s Larsen C Ice Shelf in July 2017 and has been drifting aimlessly ever since. According to the latest figures, the iceberg now measures 1,500 square miles (3,900 square kilometres) in area and 87 miles (140 km) in length. The huge scale of the iceberg is painfully evident in satellite images, as it can now be seen juxtaposed with the island. A68a isn’t very thick, measuring around 650 feet (200 meters) in depth, which matches some of the shallower areas along the island’s shelf.

Over the past several days, the iceberg, shaped like a pointing finger, has been moving clockwise. The northern, wider end of the object appears to have drifted over the shelf and into shallow waters. Klaus Strübing, a scientist with the International Ice Charting Group, fears the iceberg may be grounded, as reported by NASA’s Earth Observatory.

As of December 13, parts of A68a are in waters measuring just 250 feet (76 meters) deep. Only “time will tell” if the iceberg will dislodge itself onto the shelf, “or if the region’s complex ocean currents will carry the berg back out to sea and around the island,” according to a NASA Earth Observatory blog post.

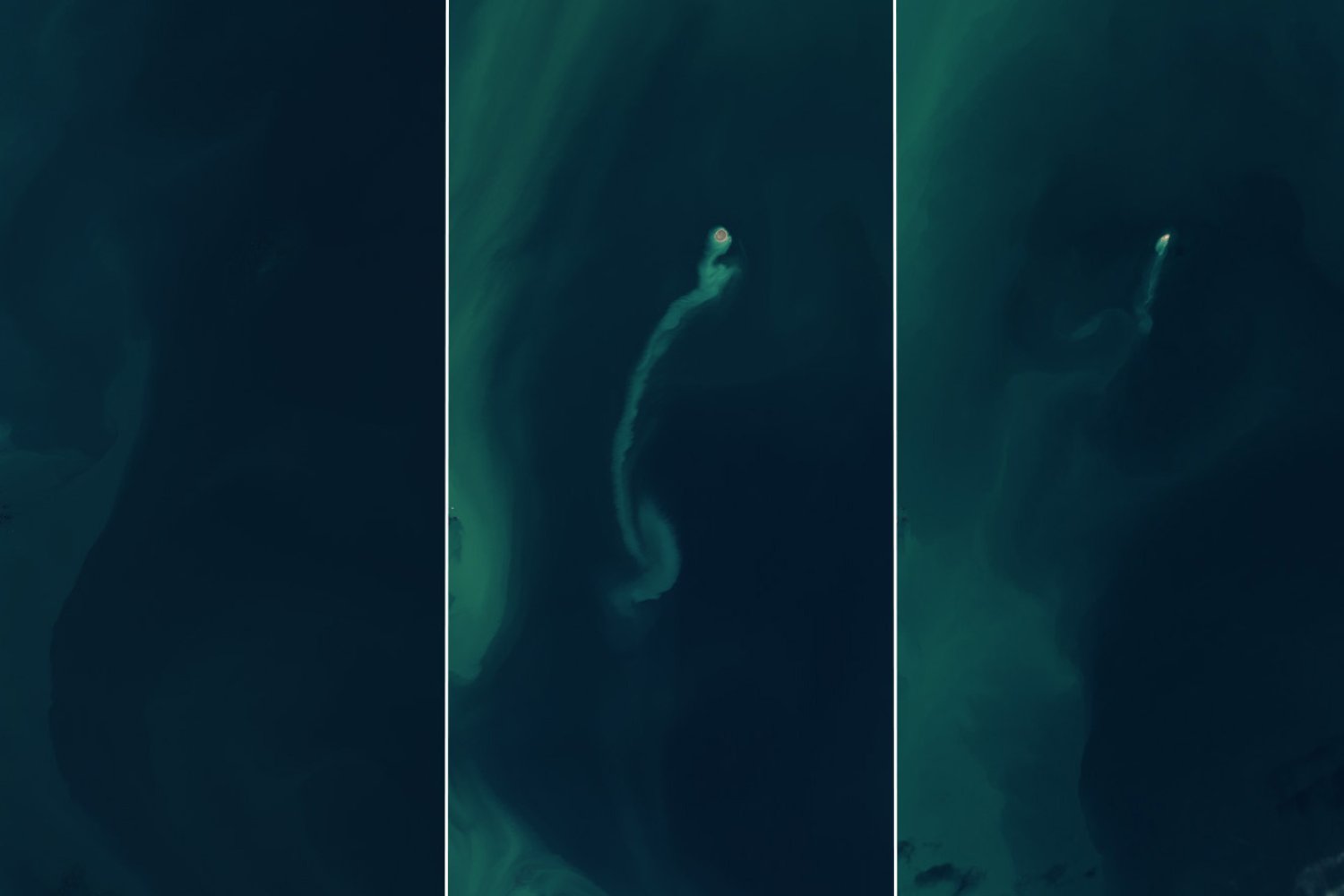

Strübing’s observations show that A68a has made a wacky journey since calving three years ago. It has been oscillating between a counterclockwise and clockwise spin, moves in fits and starts, and travels with no sense of purpose, sometimes in a straight line and sometimes in circles. As NASA points out, A68a’s path is not unlike the one taken by iceberg A43b in 2004; that berg stalled in a similar location, hung out for a few months, and then resumed its journey around the island.

Anxious to learn more about the situation, the BAS is organizing an expedition to visit the iceberg in the southern Atlantic Ocean. The team will travel aboard the RRS James Cook, which is managed by the UK’s National Oceanography Centre. Over the next several months, the scientists will evaluate the ecological impact of melting freshwater coming off the berg and potential disruptions to penguins, seals, whales, and the local fishing industry.

To that end, the team will deploy a pair of 5-foot-long (1.5-meter) robotic gliders, which will collect valuable information about the sea water on either side of the berg, such as salinity, temperature, and chlorophyll. The BAS scientists will also measure the amount of plankton in the water and then compare the data to historical records.

But it’s not all bad. Melting icebergs deliver copious amounts of dust into the ocean, which serves to fertilize ocean plankton—a critical component of the food web.

This is all quite incredible, as the saga of iceberg A68a continues to unfold. This gigantic chunk of ice, even three years into its stint, still has stories to tell.