It’s been a minute since Miguel shredded nerves at a concert in Los Angeles. On the promotion trail for his forthcoming album, Viscera, the 38-year-old singer dangled above a stage from metal hooks pierced through the flesh of his back. (Body suspension is a contemporary performance art; its practitioners commonly cite ancient ritualistic practices in India and North America as inspiration.) It was a dramatic way to underline the launch of his lovelorn, claustrophobic song “Rope”. Watching it, I’m left with more than a few questions: why would someone voluntarily hang their body from hooks? Had he done it before? Just how painful was it? I need to know.

I get the opportunity to ask when I meet Miguel on the cabana-like rooftop of the Soho Warehouse in Los Angeles, roughly half an hour away from his home in Los Feliz. It’s late August in LA, during a heatwave in which the sky is ocean blue and salty, sticky sweat oozes from your pores. Miguel hasn’t shed a drop. Which is surprising, as he arrives in a Matrix-core fit of shades, jeans and chunky black boots. I, in contrast, am not chill enough to stop myself from interrogating him about the stunt. So, as Miguel thumbs through the lunch menu, weighing his options between a burger and an ahi tuna tostada, I rattle off my questions like a precocious toddler.

Before the singer responds, he turns the tables on me, clasping his heavily ringed fingers with the open-hearted demeanour of a therapist: “How did it make you feel?” He may have seen the flurry of internet commentary, but he’s seemingly more interested in diving into the existential meaning of the practice and its impact.

With Viscera, his fifth studio album, Miguel has been on a spiritual journey: deep shadow work, meditation, and working with his therapist to achieve “more intimate personal awareness.” That journey has included body suspension, which he initially discovered when reading about how Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro found peace while hanging from metal hooks. “He’s an absolute legend,” Miguel says, adjusting his sunglasses.

He first tried suspension back in March; the concert was his third go. The first, he admits, was the most painful. And it was his fault – he opted for sharper, veteran-level hooks. “I was like, ‘Well, if we’re going to do it, we might as well just go all the way,’” he says, tossing his hands up in the air. “I guess that’s my personality – it’s all or nothing.” He was suspended under the bridge of the Mill Creek Road highway, near the San Bernardino Mountains, California, for a total of seven minutes, which he maintains “isn’t that long.” He didn’t cry during it, but found himself deep in thought afterwards. “You would be surprised, though,” he says, raising an eyebrow and sipping an iced Americano, “how you process it.”

For Miguel, who grew up between San Pedro and Inglewood with a Black mother and a Mexican father, Los Angeles has always been home. He has known that he wanted to be a recording artist since his time studying at San Pedro High School, and eventually signed with Jive Records. He broke out in 2010 with his debut album All I Want Is You, featuring the hit “Sure Thing” (which recently flew high on a second wind due to a sped-up TikTok remix), and followed it up with three more, landing not only a Grammy but also collaborations with industry titans Dua Lipa, Janelle Monáe, Tame Impala and Mariah Carey. Even as his sound has evolved, tracks such as “Sure Thing,” as well as “Adorn” and “Coffee”, have become radio mainstays. Does he mind being eternally bound to them? “Those songs are fire,” he says, raising his hands in the air. “I made it to the fucking Black barbecue. I’m at the wedding. They’re doing the fucking Electric Slide to this shit. You’ll live forever if you’re at the barbecue.”

Alongside musicians like Frank Ocean, Steve Lacy, SZA and Childish Gambino, Miguel has helped transform R&B by experimenting with fuzzy guitars, psych rock, soul, funk and punk. His aesthetic has ranged from ’70s rock star to ’90s skater boy – capturing the essence of everyone from David Bowie and Prince to the Sex Pistols – but it’s just as common to see him shirtless on stage, plucking a guitar against a set of chiselled, well-oiled abs. Miguel has leaned into this image, and his lyrics border on the pornographic: “Confess your sins to me while you masturbate,” he sings on 2015’s “The Valley”; “I want to know how to make you cry/how to make your body cream/Fill my dirty mind with your favourite erotic dream,” on 2010’s “Teach Me”. (Vibe called Miguel “the maestro of baby-making music.”)

The man behind the lyrics is disarming, toeing the line between charming and flirtatious. He’s also effortlessly self-aware, lounging on a cream-coloured sofa like Rose posing for her portrait in Titanic. When I address his divorce from ex-wife Nazanin Mandi, whom he began dating at 18 and split from in 2022, Miguel approaches it through an unfiltered lens. “I’ll be honest with you: I never wanted to be divorced,” he says. “I grew up with my ex-wife, essentially. It’s a lot of life in between there.” And there’s life after that, too. “I was not the perfect guy. I don’t think that’s a secret.” He shrugs.

When asked if they’ve been in touch, he notes that it’s important that they “heal apart,” before waxing poetic about his ex. “She’s an amazing woman. She’s strong, intelligent… a great woman. I can look at her and be like, ‘Damn, bro.’ You know?” he says. “But I can also see how things happened.” He’s excited for her to have what she deserves. “I want that for myself; I want that for her.”

Right now, Miguel has his head down in his own healing journey, both psychically and literally. I return to the initial topic of conversation: the hooks. How does he care for his piercings? “Neosporin,” he says. “I just make sure I clean the wounds, dress the wounds and let them heal.” While he’ll be sore afterwards and bleed on his sheets, Miguel accepts the pain as a lesson in mindfulness. “I’ve learned how important it is to address pain as something that passes, and that we heal from it if we choose to address it head-on,” he says. The good news? He heals quickly. The bad news? If he wants to do the stunt again, they can’t use the same entry and exit: it’s an entirely new piercing site each time. He’ll worry about that later.

Self-care and grooming are important to him. This is obvious, given that his locs and signature dewy skin require a lot of work. But Miguel’s routine, he says, is much less about three-figure face masks than it is about what he puts in his body. He eats clean and hydrates regularly, and adds Celtic salt and baking soda to his water each morning to keep his skin blemish-free. “I’ve seen a tremendous difference in my bacne,” he says, slightly embarrassed. “I’m sorry, that’s TMI.” He gets ingrown hairs, and needs to exfoliate so he doesn’t break out. (That applies to his face, too – twice a week – and he follows it up with a toner, essential oils and moisturiser.)

Unsurprisingly, Miguel is incredibly attuned to hair care. When he has locs, as he does when we sit down for lunch, he needs to keep his scalp oiled. So every few days he uses rosehip oil, which he sprays on his hair. “My hair girl made me a concoction. I don’t know what she put in it, but it’s some kind of fruits and oils and shit like that,” he says through a mouthful of tostada.

The final part of his grooming routine is for his mind: meditation. In the mornings, he’ll trek into his garden or sit up in bed to do a guided or self-guided meditation for 15 to 30 minutes, depending on how much he’s overthinking. “I can just listen to something binaural, or I’ll do brown noise,” he says. (Which, for the uninitiated, is a kind of low-frequency rumbling.)

The making of Viscera has also become part of Miguel’s healing. He ended up touring for two years after the release of his fourth record, 2017’s War & Leisure. During that time his grandmother died, he got married, then his grandfather died. It was a lot. Then, he took a brief break before jumping back into the studio in 2020. After just two weeks back on the grind, he needed to clear his head and went on a trip to the liquor store, where he got a call from his cousin.

“My phone was blowing up like, ‘Yo. We got to lock down,’ and I was like, ‘What?’” Miguel says. He spent that time in isolation, dealing not only with the impact of coronavirus but also with all of the social unrest following police brutality, the Black Lives Matter protests and the murder of George Floyd. “It seemed like we were spiralling,” he says. That added two and a half years to the recording process. Plus, there was his divorce. Counting backwards from 2017, he does the maths aloud. “That there eats up what, five years?” he sighs. He can’t really blame the delay on one thing. “More than anything, it wasn’t the right time for me.”

The sonic palette of Viscera was shaped by Beat poets, such as Charles Bukowski, and, specifically, contemporary writer Carmen Maria Machado’s collection of short stories Her Body and Other Parties. Miguel gravitated, he says, towards creatives who “critique the reality of life.” The allure of Machado’s work came from its postapocalyptic themes and an emotional undercurrent that was sexual. “Which I enjoyed, of course,” he laughs. “Big surprise.”

American rapper Vic Mensa approaches the table to give Miguel a hug. He, like the rest of the world, has a laundry list of questions about the big suspension stunt, but as quickly as he appeared, he’s gone, having made plans to hang out and drive around together.

Miguel doesn’t miss a beat and returns to the topic, citing inspiration from Kurt Vonnegut’s Welcome to the Monkey House, a short story collection that he says riffs on postapocalyptic life and the way that the public can be controlled by the media and government.

During Covid, Miguel found his awareness shift to focus on his own emotional maturity. “I knew that there was some work that needed to be done there before I plugged in,” he says of making Viscera. He needed to grow up. His personal life was changing, and so were his views – he needed to better understand the impetus behind his choices. “It took some time to find the music I could really get behind and be passionate about,” he says, dipping a tortilla chip into a small mountain of guacamole. “It felt important.”

Viscera, he says, has “a more alternative tone and energy” than his previous work. There are Bloc Party-like interludes, punk vocals, reverb guitars, ambient trap melodies and sinister drumming. Scrolling through his phone, Miguel lights up and chuckles as he recalls the artists and genres that influenced Viscera: hard techno, the San Pedro art-punk band Minutemen, Nine Inch Nails, Flying Lotus, Flume and Sophie (“Rest in peace”).

While he’d rather remain mostly tight-lipped about collaborations, Miguel enlisted Lil Yachty for “Number 9”, a retro-futuristic experimental trip-hop piece, and A$AP Rocky for another undisclosed track. But the record, he says, really began with “Rope,” which allowed Miguel to acknowledge the darkness in life cycles. The rest of the album tackles a spectrum of personal topics. “The Killing,” a downtempo R&B number with high-pitched harmonies that channels the psych-rock licks of Tame Impala, is what Miguel calls “the tone of my sexuality.” The more radio-friendly “Comma Karma” is the ethos of the album, where Miguel comes to terms with his own mortality. The stripped-back ballad “Always Time,” he says, is “the best summary of the evolution of my relationship with my ex. I thought there was always time, and I thought there would always be time. Sometimes really loving is about letting go.”

The album’s imminent release is a late birthday gift to himself. It is, Miguel says, a record about “the beautiful, violent nature of change [and] growth.” Change can be painful, but pain itself can be part of growing. When Miguel first started body suspension, he found that the moment the hooks pierced the skin wasn’t the worst part (he has a number of tattoos and is familiar with pain). It was actually moving after the hooks were in. So excruciating was it that Miguel almost gave up at the five-minute mark, but his teacher stood in front of him and said: “Everyone, their first time, has this moment where they have to decide to break through.” His instructor’s words helped Miguel, a “chronic overthinker”, to “let go of this need to be in control of everything.” Other people saw pain, but for him, it was a release.

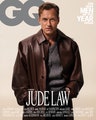

Styled by Maleeka Moss

Make-up by Holly Silius

Hairstyling by Antoine Martinez

Tailoring by Gulsen Kan

Production by Early Morning Riot

Lead image credits: Jacket by Random Identities at Paumé Los Angeles. Trousers by Courrèges. Belt (top) by Helmut Lang Archival at Artifact NY. Belt (middle) by Helmut Lang Archival at Wild West Social House. Belt (bottom) by Raf Simons Archival at Wild West Social House. Necklaces by Cruize at Paumé Los Angeles. Earring by Bond Hardwear. Boots by Expired Rags.