What is melanoma?

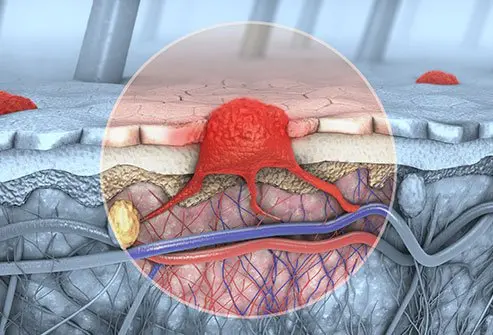

Melanoma is a cancer that develops in melanocytes, the pigment cells present in the skin. It can be more serious than the other forms of skin cancer because of a tendency to spread to other parts of the body (metastasize) and cause serious illness and death. About 50,000 new cases of melanoma are diagnosed in the United States every year.

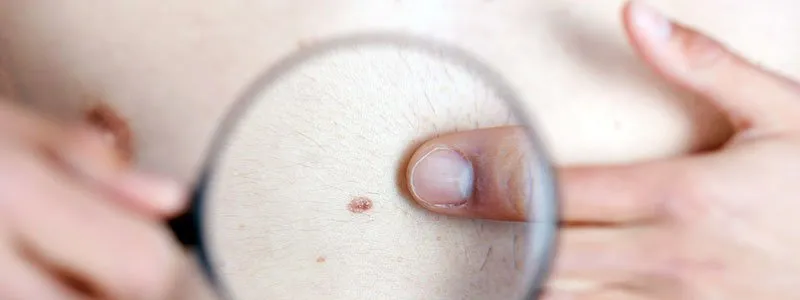

Because most melanomas occur on the skin where they can be seen, patients or their spouses are often the first to detect suspicious tumors. Early detection and diagnosis are crucial. Caught early, most melanomas can be cured with relatively minor surgery.

This article is written from the standpoint of the patient. Instead of describing the disease in exhaustive detail, the article focuses on answering the questions: "How do I know if I have melanoma?" and "Should I be checked for it?"

What is recurrent melanoma?

Recurrent melanoma refers to a recurrence of a tumor at the site of removal of a previous tumor, such as in, around, or under the surgical scar. It may also refer to the appearance of metastatic melanoma in other body sites such as skin, lymph nodes, brain, or liver after the initial tumor has already been treated.

Recurrence is most likely to occur within the first five years, but new tumors felt to be recurrences may show up decades later. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish recurrences from new primary tumors.

What is metastatic melanoma?

Metastatic melanoma is melanoma that has spread beyond its original site in the skin to distant tissue sites. There are several types of metastatic melanoma. There may be spread through the lymphatic system to local lymph nodes. This may show up as swollen lymph glands (usually painless) or as a string of skin tumors along a lymphatic chain.

Melanoma may also spread through the bloodstream (hematogenous spread), where it may appear in one or more distant sites, such as the lungs, liver, brain, remote skin locations, or any other body location.

What are the types of melanoma?

The main types of melanoma are as follows:

- Superficial spreading melanoma: This type accounts for about 70% of all cases of melanoma. The most common locations are the legs of women and the backs of men, and they occur most commonly between the ages of 30-50. (Note: Melanomas can occur in other locations and at other ages, as well.) These melanomas are flat or barely raised and have a variety of colors. Such melanomas evolve over one to 5 years and can be readily caught at an early stage if they are detected and removed. An "in situ" melanoma (malignant melanoma in situ) refers to a very thin superficial spreading melanoma that does not extend deeper than the junction of the dermis and epidermis, the normal location for melanocytes.

- Nodular melanoma: About 20% of melanomas are thick, blue-black to purplish lumps. They may evolve faster and are more likely to spread. Untreated superficial spreading melanomas may become nodular and invasive.

- Lentigo maligna: Unlike other forms of melanoma, lentigo maligna tends to occur in places like the face, which are exposed to the sun constantly rather than intermittently. Lentigo maligna looks like a large, irregularly shaped, or colored freckle and develops slowly. It may take many years to evolve into a more dangerous melanoma or may never become a more invasive form. Because of the unpredictability of future behavior, removal is recommended.

Other rarer forms of melanoma may occur, for example, under the nails (subungual), on the palms and soles (acral lentiginous), uveal or choroidal (ocular), oral or other mucosal areas such as the vulva or penis, or sometimes even inside the body such as the brain.

What are the causes and risk factors for melanoma?

Individual sunburns do raise one's risk of melanoma. However, slow daily sun exposure, even without burning, may also substantially raise someone's risk of skin cancer.

Factors that raise one's risk for melanoma include the following:

- Caucasian (white) ancestry

- Fair skin, light hair, and light-colored eyes

- A history of intense, intermittent sun exposure, especially in childhood (This would include tanning booths.)

- Many (more than 100) moles

- Large, irregular, or "funny-looking" moles

- Close blood relatives -- parents, siblings, and children -- with melanoma

The presence of close (first-degree) families with melanoma is a high-risk factor, although looking at all cases of melanoma, only 10% of cases run in families.

Having a history of other sun-induced skin cancers raises one's risk of melanoma because they are markers of long-term sun exposure. The basic cell type is different, however, and a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma cannot "turn into melanoma" or vice versa.

How can people estimate their level of risk for melanoma?

The best way to know one's risk level is to have a dermatologist perform a full body examination. That way one will find out whether the spots one has are moles and, if so, whether they are abnormal in the medical sense. More darkly pigmented individuals are at less risk of skin cancers in general and melanoma in particular.

The medical term for such moles is atypical. This is a somewhat confusing term, because among other things the criteria are not clear, and it's not certain that an atypical mole is necessarily precancerous. Patients who have lots of "atypical moles" (more than 24) do have a higher risk for developing melanoma but not necessarily within one of their existing funny-looking moles. It may be a challenge to find the "baby melanoma" in the middle of a back full of large, dark, or irregular moles. If someone has such moles, a doctor will recommend regular surveillance and may recommend a biopsy of the most unusual or worrisome-looking moles.

Sometimes, one learns at a routine skin evaluation that one does not necessarily need annual routine checkups. In other situations, a doctor may recommend regular checks at 6-month or yearly intervals.

QUESTION

Self-examination is important in the detection of skin cancer. See AnswerWhat are symptoms and signs of melanoma?

Spots on the skin

Guideline # 1: Nobody can conclusively diagnose one's self. A physician should examine new spots on the skin that itch, bleed, or enlarge. It is always better to be safe than sorry so if there is concern about a particular skin lesion see a medical specialist.

Everybody gets spots on their skin. The older we are, the more spots we have. Most of these spots are benign. That means they are neither cancerous nor on the way to becoming cancerous. These may include freckles, benign moles, collections of blood vessels called cherry angiomas, or raised, irregular, pigmented bumps on the skin called seborrheic keratoses.

Moles

Guideline # 2: The vast majority of moles are benign lesions that do not turn into anything else. Most melanomas do not arise in preexisting moles. For that reason, having all of one's moles removed to "prevent melanoma" does not make sense.

Some people are born with moles (the medical name is "nevus," plural "nevi"). Almost everyone develops them, starting in childhood. On average, white Europeans have about 25 moles, though some have fewer and others many more. Moles may be flat or raised, and they may range in color from tan to light brown to black. Moles may lose their color and end up flesh-colored. It is unusual to develop new pigmented moles after age 35.

Melanoma

Guideline # 3: A changing spot may be a problem, but not every change means cancer. A mole may appear and then get bigger or become raised but still be only a mole. It is normal for many moles to start flat and dark, become raised and dark, and then later lose much of their color. This process takes many years.

Most public health information about melanoma stresses the so-called ABCDEs:

- Asymmetry: One half of the mole is different from the other half.

- Border irregularity: The spot has borders that are not smooth and regular but uneven or notched.

- Color: The spot has several colors in an irregular pattern or is a very different color than the rest of one's moles.

- Diameter: The spot is larger than the size of a pencil eraser (6 mm).

- Evolving: The mole is changing in size, shape, color, or overall texture. This may also include new bleeding.

These guidelines can be helpful, but the problem is that many pigmented lesions of the skin are not perfectly symmetrical in their shape or color. Many spots, which seem to have one or more of the ABCDEs, are just ordinary benign skin tumors and are not dangerous. Additionally, some melanomas do not fit this description but may still be spotted by a primary care physician or dermatologist. Not all melanomas have a color or are raised above the skin surface.

What if the skin changes are rapid or dramatic?

Guideline # 4: The more rapid and dramatic the change, the less serious the problem.

When changes such as pain, swelling, or even bleeding come on rapidly, within a day or two, they are likely to be caused by minor trauma, often a kind one doesn't remember (like scratching the spot while sleeping). If a spot changes rapidly and then goes back to the way it was within a couple of weeks, or falls off altogether, it is not likely to represent anything serious.

Nevertheless, this would be a good time to say once again: Nobody can diagnose him- or herself. If one sees a spot that looks as though it is new or changing, show it to a doctor. If one sees a spot that doesn't look like one's other spots, it should be evaluated.

What are the signs of symptoms of metastatic melanoma?

Signs and symptoms depend upon the site of metastasis and the number of tumors there. Metastases to the brain may first appear as headaches, unusual numbness in the arms and legs, or seizures.

- Spread to the liver may be first identified by abnormal blood tests of liver function long before the patient has jaundice, a swollen liver, or any other signs of liver failure.

- Spread to the kidneys may cause pain and blood in the urine.

- Spread to the lungs may cause shortness of breath, other trouble breathing, chest pain, and continuous cough.

- Spread to bones may cause bone pain or broken bones called pathologic fractures.

A very high tumor burden may lead to fatigue, weight loss, weakness, and, in rare cases, the release of so much melanin into the circulation that the patient may develop brown or black urine and have their skin turn a diffuse slate-gray color. The appearance of multiple blue-gray nodules (hard bumps) in the skin of a melanoma patient may indicate widespread melanoma metastases to remote skin sites.

Health News

- Check Your Pantry, Lay's Classic Potato Chips Recalled Due to Milk Allergy Risk

- California Declares Bird Flu Emergency as Outbreak in Cows Continues

- Not Just Blabber: What Baby's First Vocalizations and Coos Can Tell Us

- Norovirus Sickens Hundreds on Three Cruise Ships

- FDA Updates Meaning of 'Healthy' on Food Labels

More Health News »

More Health News »

How do healthcare professionals diagnose melanoma?

Most doctors diagnose melanoma by examining the spot causing concern and performing a minor surgical procedure called a biopsy. A skin biopsy refers to removing all or part of the skin spot under local anesthesia and sending the specimen to a pathologist for analysis. A small shave or punch biopsy which may be adequate for the diagnosis of other types of skin cancer is not the best for melanoma. To diagnose melanoma, the best biopsy is one that removes the entire extent of the visible tumor. Fine-needle aspiration may have a role in evaluating a swollen lymph node or a liver nodule but is not appropriate for the initial diagnosis of a suspicious skin lesion.

It is no longer recommended to do large batteries of screening tests on patients with thin, uncomplicated melanoma excisions, but patients who have had thicker tumors diagnosed or who already have signs and symptoms of metastatic melanoma may need to have MRIs, PET scans, CT scans, chest X-rays, or other X-rays of bones when there is a concern of metastasis.

The biopsy report may show any of the following:

- A benign condition requiring no further treatment, such as a regular mole

- An atypical mole, depending on the judgment of the doctor and the pathologist, may need a conservative removal (taking off a little bit of normal skin all around just to make sure that the spot is completely out).

- A thin melanoma requiring surgery

- A thicker melanoma requires more extensive surgery or extra tests in which the lymph nodes are examined. Sentinel node biopsy is a procedure in which a dye or radioactive tracer is injected into the tumor site and then draining lymph nodes are identified and removed for microscopic examination. A negative result suggests there has not yet been spread through the lymphatic chain for that area of skin. A positive result suggests there may be other lymph nodes involved. Since the removal of draining lymph node basins causes physical problems and does not seem to improve longevity it is no longer generally recommended.

Some doctors are skilled in a clinical technique called epiluminescence microscopy (also called dermatoscopy or dermoscopy). They may use a variety of instruments to evaluate the pigment and blood vessel pattern of a mole without having to remove it. Sometimes the findings support the diagnosis of possible melanoma, and at other times, the findings are reassuring that the spot is nothing to worry about. The standard for a conclusive diagnosis, however, remains a pathologic examination of a skin biopsy.

What are the stages of melanoma?

The most useful criterion for determining prognosis is tumor thickness. Tumor thickness is measured in fractions of millimeters and is called Breslow's depth. The thinner the melanoma, the better the prognosis. Any spread to lymph nodes or other body locations dramatically worsens the prognosis. Thin melanomas, those measuring less than 0.75 millimeters when examined microscopically, have excellent cure rates, generally with local surgery alone. For thicker melanomas, the prognosis is guarded.

Melanoma is staged according to thickness, ulceration, lymph node involvement, and the presence of distant metastasis. The staging of cancer refers to the extent to which it has spread at the time of diagnosis, and staging is used to determine the appropriate treatment.

- Stages 1 and 2 are confined to the skin only and are treated with surgical removal with the size of margins of normal skin to be removed determined by the thickness of the melanoma.

- Stage 3 refers to a melanoma that has spread locally or through the usual lymphatic drainage.

- Stage 4 refers to distant metastases to other organs, generally by spread through the bloodstream.

What are melanoma treatment options?

In general, early localized melanoma is treated by surgery alone.

- Doctors have learned that surgery does not need to be as extensive as was thought years ago.

- When treating many early melanomas, for instance, surgeons only remove 1 centimeter (less than ½ inch) of the normal tissue surrounding the melanoma.

- Deeper and more advanced cancers may need more extensive surgery.

- Depending on various considerations (tumor thickness, body location, age, etc.), the removal of nearby lymph nodes may be recommended.

- For advanced disease, when melanoma spreads to other parts of the body, treatments using immunotherapy or chemotherapy are often recommended. Many of these new treatments have produced rather impressive improvements in longevity.

An Internet search will name a variety of home remedies and natural products for the treatment of skin cancers, including melanoma. These include the usual topical and systemic antioxidants and naturopathic immune stimulators. No scientific data is supporting any of these, and their use may lead to unnecessary delay in better-established treatments, possibly with tragic results.

What are the treatments for metastatic melanoma?

Historically, metastatic and recurrent melanoma have been poorly responsive to chemotherapy. Immunotherapy, in which the body's immune system is energized to fight the tumor, has been a focus of research for decades. A variety of newer medications target different points in the pathways of melanoma cell growth and spread. While the most appropriate use of these medications is still being defined, the best treatment for melanoma remains complete surgical excision while it is still small, thin, and has not yet had a chance to spread.

Initial therapies to stimulate the immune system to help contain metastatic melanoma included infusions of interferon-alpha and interleukin-2 (both parts of the immune response to cancer and infection), and a few patients have responded to these therapies. There has, however, been an explosion recently in the approval of several targeted therapies that act on specific stages in the cell cycle, especially those of abnormal cells, and affect the growth processes of the tumor cells.

Drugs that inhibit the kinase enzymes necessary for cell reproduction include cobimetinib (Cotellic) and trametinib (Mekinist). Others target the signals for cell growth from abnormal BRAF genes and the enzymes they drive. Such medications in this family include dabrafenib (Tafinlar), vemurafenib (Zelboraf), and nivolumab (Opdivo). Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) blocks the tumor's ability to inhibit T-cell activity. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) works directly on the T-lymphocyte pathway to activate the immune system.

Many of these medications are now being used in combinations to get better therapeutic effects than they would by themselves. All of these medications have significant side effects, including some that are life-threatening, and are indicated only for stage 3 tumors to try to prevent recurrence and spread and stage 4 metastatic tumors that are no longer amenable to surgery.

What are the survival rates for metastatic melanoma?

Survival rates for melanoma, especially for metastatic melanoma, vary widely according to many factors, including the patient's age, overall health, location of the tumor, particular findings on the examination of the biopsy, and of course the depth and stage of the tumor. Survival statistics are generally based on 5-year survival rates rather than raw cure rates.

Much of the success reported for the targeted therapies focuses on disease-free time because in many cases the actual 5-year survival is not affected. It is hoped that the combination therapy discussed above will change that.

- For stage 1 (thin melanoma, local only), 5-year survival is ≥ 90%.

- For stage 2 (thicker melanoma, local only), 5-year survival is 80%-90%.

- For stage 3 (local and nodal metastasis), 5-year survival is around 50%.

- For stage 4 (distant metastasis), 5-year survival is 10%-25% depending upon sex and other demographic factors.

Subscribe to MedicineNet's Cancer Report Newsletter

By clicking "Submit," I agree to the MedicineNet Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. I also agree to receive emails from MedicineNet and I understand that I may opt out of MedicineNet subscriptions at any time.

What methods are available to help prevent melanoma?

- Reducing sun exposure: Avoidance of ultraviolet light exposure, including exposure in tanning booths, is the best means of helping to prevent melanoma, followed by wearing hats and opaque clothing, and then followed by broad-spectrum waterproof sunscreens applied liberally to exposed skin. The consensus among dermatologists is that sunscreens are helpful and are certainly preferable to unprotected sun exposure. (Despite sensational articles in the popular press, there is no credible evidence that sunscreens can cause melanoma. Data to indicate increased melanoma risk did not take into consideration that the sunscreens used by the subjects [at least as well as they could remember after decades] were far inferior to current products, which usually have much higher ultraviolet B SPF protection as well as ultraviolet A protection.)

- Early detection: Get one's skin checked at least once. Then, if it is recommended, have one's skin checked regularly. The American Academy of Dermatology sponsors free skin cancer screening clinics every May all over the country. Special "Pigmented Lesion Clinics" have also been established in many medical centers to permit close clinical and photographic follow-up of patients at high risk.

- Screening of high-risk individuals: Anyone at high risk, such as anyone with a close relative who has melanoma, should be screened by a doctor for melanoma.

What research is being done on melanoma?

Research in melanoma is headed in three directions: prevention, more precise diagnosis, and better treatment for advanced disease.

- Prevention: Public education and more widely available screening clinics can increase public awareness of the need for sun avoidance, sunscreen use, avoidance of tanning booths, and early detection of suspicious spots.

- More precise diagnosis: Newer experimental techniques, such as the confocal scanning laser microscope, may help doctors make more certain calls on borderline or suspicious spots without having to biopsy.

- Better treatment for advanced disease: Because conventional chemotherapy has been disappointing with melanoma, researchers have turned their attention to biological treatments of advanced melanoma to stimulate the body's immune response against the tumor. These new biologic treatments include immune checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and drugs that target cell growth based on genetic changes the melanoma. Many of these treatments are still investigational and intended for patients with widespread, recurrent life-threatening diseases.

Where can people get more information about melanoma?

- For further information about all aspects of melanoma, please visit the American Academy of Dermatology.

- One can obtain information about free skin cancer screening clinics held by the American Academy of Dermatology every May all over the country.

Chae, Young Kwang, Michael S. Oh, and Francis J. Giles. "Molecular Biomarkers of Primary and Acquired Resistance to T-Cell-Mediated Immunotherapy in Cancer: Landscape, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions." The Oncologist (2017): 1-12.

Mayer, J.E., S.M. Swetter, T. Fu, and A.C. Geller. "Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part I. Epidemiology, high-risk groups, clinical strategies, and diagnostic technology." J Am Acad Dermatol 71.4 Oct. 2014: 599.e1-599.e12; quiz 610, 599.e12.

Mayer, J.E., S.M. Swetter, T. Fu, and A.C. Geller. "Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007-2013) and future directions: Part II. Screening, education, and future directions." J Am Acad Dermatol 71.4 Oct. 2014: 611.e1-611.e10; quiz 621-2.

Schadendorf, Dirk, et al. "Melanoma." Nature Reviews: Disease Primers 1 (2015): 1-20.

Swetter, Susan M., et al. "Guidelines of Care for the Management of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma." J Am Acad Dermatol 2018.

Top Melanoma Related Articles

Biological Therapy

Biological or biologic therapy is a type of treatment used to stimulate or restore the ability of the body's immune system. Other names for this type of therapy include biotherapy or immunotherapy. It is used to treat cancer and other conditions, as it helps the body fight infection and disease.

What are the Risks or Complications of a Bone Marrow Procedure?

A bone marrow biopsy involves using a large needle to extract a sample from the bone marrow to diagnose blood cancers and other conditions. Bone marrow is often extracted from the pelvic bone. Potential risks of the procedure include pain and soreness and, more rarely, bleeding and infection.

Cancer

Cancer is a disease caused by an abnormal growth of cells, also called malignancy. It is a group of 100 different diseases, and is not contagious. Cancer can be treated through chemotherapy, a treatment of drugs that destroy cancer cells.

CT Scan (Computerized Tomography)

A CT scan is an X-ray procedure that combines many X-ray images with the aid of a computer to generate cross-sectional and three-dimensional images of internal organs and structures of the body. A CT scan is a low-risk procedure. Contrast material may be injected into a vein or the spinal fluid to enhance the scan.

Chest X-Ray

Chest X-Ray is a type of X-Ray commonly used to detect abnormalities in the lungs. A chest X-ray can also detect some abnormalities in the heart, aorta, and the bones of the thoracic area. A chest X-ray can be used to define abnormalities of the lungs such as excessive fluid (fluid overload or pulmonary edema), fluid around the lung (pleural effusion), pneumonia, bronchitis, asthma, cysts, and cancers.

Female Screening Tests

What is a health screening? Why is it important to know your blood pressure? How long will your health screening take? Learn about wellness screenings for women for breast cancer, HIV, diabetes, osteoporosis, skin cancer, and more.

Moles

Moles are small skin growths that may appear flat or raised and are often tan, brown, black, reddish brown, or skin colored. They are typically about the size of a pencil eraser. There are three types of moles. Monthly skin self-exams are essential in the early detection of abnormal moles and melanomas.

Moles Picture

Moles are growths on the skin that are usually brown or black. See a picture of Moles and learn more about the health topic.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scan)

MRI (or magnetic resonance imaging) scan is a radiology technique which uses magnetism, radio waves, and a computer to produce images of body structures. MRI scanning is painless and does not involve X-ray radiation. Patients with heart pacemakers, metal implants, or metal chips or clips in or around the eyes cannot be scanned with MRI because of the effect of the magnet.

Skin Cancer Quiz

What causes skin cancer? Take our Skin Cancer Quiz to learn about the risks, symptoms, causes, and treatments for this common skin condition that affects millions of people worldwide.

Skin Cancer Slideshow

Discover the causes, types, and treatments of skin cancer. Learn how to prevent skin cancer and how to check for melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. Also, find out how to spot the early signs of skin cancer.

Skin Tag

A skin tag is a small benign growth of skin that projects from the surrounding skin. Skin tags can vary in appearance (smooth, irregular, flesh colored, dark pigment, raised). Skin tags generally do not cause symptoms unless repeatedly irritated. Treatment for skin tag varies depending on the location on the body.

Sun-Damaged Skin

See how sun damaged skin can cause wrinkles, moles, melanoma (skin cancer) and more. Explore images of squamous cell carcinoma and the early signs of skin cancer.

Symptoms of 12 Serious Diseases and Health Problems

Learn how to recognize early warning signs and symptoms of serious diseases and health problems, for example, chronic cough, headache, chest pain, nausea, stool color or consistency changes, heartburn, skin moles, anxiety, nightmares, suicidal thoughts, hallucinations, delusions, lightheadedness, night sweats, eye problems, confusion, depression, severe pelvic or abdominal pain, unusual vaginal discharge, and nipple changes.The symptoms and signs of serious health problems can be caused by strokes, heart attacks, cancers, reproductive problems in females (for example, cancers, fibroids, endometriosis, ovarian cysts, and sexually transmitted diseases or STDs), breast problems (for example, breast cancer and non-cancer related diseases), lung diseases (for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or COPD, lung cancer, emphysema, and asthma), stomach or digestive diseases (for example, cancers, gallbladder, liver, and pancreatic diseases, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn's disease), bladder problems (for example, urinary incontinence, and kidney infections), skin cancer, muscle and joint problems, emotional problems or mental illness (for example, postpartum depression, major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mania, and schizophrenia), and headache disorders (for example, migraines, or "the worst headache of your life), and eating disorders and weight problems (for example, anorexia or bulimia).

The Skin: 7 Most Important Layers and Functions

The skin is the largest organ in the body and it covers the body's entire external surface. It is made up of seven layers. The first five layers form the epidermis, which is the outermost, thick layer of the skin. The hypodermis is the deepest layer of skin situated below the dermis.

Feet & Your Health

Foot pain and heel pain can be signs of serious health problems. Discover information about cold feet, itchy feet, burning feet and swollen feet. Learn how psoriasis, lung problems, and diabetes can cause foot symptoms.