It's the Star Wars spin-off that took everybody by surprise. After a conveyor belt of familiar character stories and cautious off-shoots, Andor has broken new ground in the IP era, using its source material to build out a multi-faceted action-espionage thriller cut through with its grounded examination of how the fascistic Empire was allowed to rise in the first place. The answer? Not the inherent evil of a handful of history makers but forces all the more insidious: unrelenting aspiration, moral ambivalence and coercive state terror.

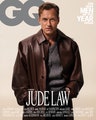

Now ten episodes in, the series has seen its eponymous hero transform from apolitical nobody to reluctant mercenary, and now, to the proto-revolutionary who would go on to make the ultimate sacrifice for the freedom of the galaxy. “How do you get there? That was, for me, the entire pitch,” Tony Gilroy, the showrunner of Andor, tells GQ. Here, we speak to Gilroy about his initial intent with the series, its brilliant ensemble of performers winning acclaim across the board, and what might come of Cassian in the final two episodes.

GQ: Two decades ago, with The Phantom Menace, George Lucas tried to inject some political maturity into Star Wars — we all remember that opening crawl, where it's talking about trade routes and blockades. Audiences hated it. Andor has been acclaimed, not least for its lens on the political and ideological stuff undergirding of the Empire. So what's different?

Tony Gilroy: I think I look at it differently. Taking away the political lens, just look at what the Marvel Universe did with their stories: they're opening all sorts of new lanes, because the audience can handle various bandwidth. I can't believe the elasticity of some of the things that they do. So I don't think the big shift for our show is that it's political.

The big shift is that it's an entirely different approach to storytelling really: it's grounded, it's serious. It's a behaviour show, it's an actor show. You have all these complicated, interweaving plots, all of these different characters coming together. I mean we're seeing right now, just watching the conversations on social media, it's fascinating to see all the various points of view — people coming fresh at it who haven't seen Star Wars before, all the way to the farthest end of the spectrum, who are really beholden to the original.

Even so, I don't think we've had a Star Wars tie-in that gets into the backroom bureaucracy of the Empire—

In [The Empire Strikes Back] you do! There's bureaucratic meetings in Empire.

Sure, but I don't think it's nearly as focal as in Andor. So why'd you want to get into the nitty gritty?

I mean, I don't have another way of doing it. It doesn't matter if I'm doing… I've done a lot of different kinds of movies over the last 35 years, all kinds of movies, and even movies that I've come into fix and worked on for just a couple weeks here and there. And my approach is always the same — I can't write a scene unless everything's real to me, I just can't.

I can write very, very quickly if everything is real to me, if I understand it and what everybody's doing, but if all of a sudden somebody presents you with something that's arbitrary and in the air, it's impossible! I'm either limited or blessed, or a combination of both. It doesn't matter if it's orcs or dragons or, you know, the Warsaw Ghetto, for me it's the same process, it's the same buy-in. [Lucasfilm president] Kathy Kennedy knew, and everybody else knew, that's what they were gonna get — I wasn't gonna change who I was to come in and do the show.

I think there's a conception that, from the beginning, Andor was planned as an adultified look at how this fascistic autocracy rose in the world of Star Wars. But that doesn't sound so much like your pitch for the show so much as that's how you always work.

It was always a character pitch! It was like: who is this guy in Rogue One, who is just all singing, all dancing, just a consummate leader, who has all of these complicated leadership abilities, and tactical abilities, and he changes his mind, and he seduces, and he lies, and he's inspired — then the guy, like, sacrifices himself! With an open heart. How do you get there? That was, for me, the entire pitch.

You've seen the end of [episode ten] — that's kind of like his Master's degree in leadership. Before that, he'll help out, but it's always been, I'm only staying six more weeks. Now he's not only leading a mini-revolution, but he's doing it in the most sophisticated way possible, which is that he's saying, “Oh, here's a guy — [Andy Serkis' Kino Loy] — who has better leadership skills than I do, he has to be the one…” and inspiring him. You're watching him become something, and my bias is about that. Everything else comes from that.

As Syril (Kyle Soller) and Dedra (Denise Gough) come together, it's interesting to see how they differ in their perception of the Empire, as much as they both serve it. Syril doesn't exactly scream “flag-waving ideologue,” but Dedra's space fash through and through.

I don't think Syril has an ideology. He's a man in search of a place, he's a man in search of confirmation. I think he's the kind of person for who chaos is so terrifying that order becomes a religion. And if order represents fascism, he'll do that; if order represents a commune in Oregon, he would do that too.

If you go back and look at — God, this is a weird thing to say — I don't know the year, but there was a Hitler movie called Max [2002]. And he was a painter, it's just after World War One, and you realise the guy could go either way. Listen, that's the thesis of the movie, I don't know if that's historically perfect, but you're watching him going, Is he going to become an avant-garde painter? Or is he gonna go speak at the beer hall? You know, which one is winning?

I keep thinking about Arendt's idea of the banality of evil with him: he just so perfectly embodies that aspirational cog in a terrifying machine. He just wants to do a good job regardless of what it is he serves, like you say, because that's the meaning he craves.

The banality of evil is a T-shirt that a lot of people on our show could be wearing. [Laughs.]

The three episodes in Narkina 5, this prison-slash-concentration camp, are my favourites of the series so far. The Cassian who enters is very different to the guy who leaves. What is it about the prison that changes him so irrevocably?

The prison is a world, isn't it? It's its own private world, a complete societal world. And my god, they're basically saying to him, This is where you're gonna live for the rest of your life. This is the system you're in for the rest of your life. This is your world. So what are you going to do about it?

It's similar for Kino, right? He's a collaborator, he seemingly believes in the idea of the Empire, at least in the idea of just order. But then he realises that it's all a sham.

Yeah. For me, Kino's story is one about faith. It's a religious story in a way: his afterlife is getting out, right? “When this is over, I'm getting out. There's going to be an end to this. I'm going to get out of this.” And that's the church that he's praying at. And my God, he's a zealot for that church. And you get to watch that faith be crushed. What do you do when faith disappears and has to subplanted by something else? And that's what you're seeing there. I don't wanna put people in a frame of mind when they watch it, but to me, Kino's non-political, it's much more philosophical and religious.

Lending into that idea: he can't swim, so he can't escape as everyone else does.

And he knew that, didn't he? So you thought he was being heroic, but you didn't realise how heroic he was really being.

Now he and Cassian are separated, but presumably he isn't trapped there forever…

He doesn't die, does he? You don't see it.

No. Unless he drowns. Cassian escapes, though. What's next for him?

That's why you're paying that nine dollars a month man! Tune in next week.